Hispaniolan Amazon Parrot (Amazona ventralis)

The Hispaniolan Amazon Parrot (Amazona ventralis) stands out from other amazon parrots with its vibrant green plumage accented by bright splashes of red, blue, and white. As you read on, you’ll uncover fun facts about this parrot’s appearance, behavior, habitat, and place in history.

Scientific Background

The Hispaniolan Parrot’s scientific name comes from the Greek word “amazōn”. Historians believe this refers to the female warriors of the ancient Scythian tribe. Early European explorers likened these brightly colored parrots to the fiercely strong Amazons of mythology. The species name “ventralis” refers to the parrot’s red belly patch.

This parrot is 1 of 3 species descending from the Yellow-crowned Amazon (Amazona ochrocephala) in Central America. Scientists believe the Hispaniolan Parrot’s ancestors colonized the Caribbean island of Hispaniola around 760,000 years ago.

The species made its first documented appearance in the written record in the 1500s. Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo chronicled the parrot in his book “Natural History of the Indies”. He dubbed them “higuacas” after the native Taíno people’s word for these birds.

At a Glance

- Length: 28 cm (11 in)

- Wingspan: unknown

- Weight: 250 g (8.8 oz)

- Lifespan: Up to 60 years

- Range: Hispaniola, Puerto Rico

- Habitat: Forests, woodlands

- Diet: Seeds, fruits, nuts

- IUCN Status: Vulnerable

- Unique Trait: White eye ring

The Hispaniolan Parrot has an unmistakable appearance. Its bright plumage and unique facial markings help set it apart from other parrots in its range. In the next section, we’ll cover some of this parrot’s stand-out physical features.

History and Taxonomy

The Hispaniolan Parrot has a long history intertwined with the native peoples and explorers of the Caribbean. Scientists have pieced together this species’ taxonomic timeline from historical accounts, fossil evidence, and genetic analysis.

First Discovery

As mentioned in the introduction, Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo made the first written record of the Hispaniolan Parrot in the 1500s. However, the indigenous Taíno people, who inhabited Hispaniola before European contact, had long known about this vivid green parrot. Their name for it, “higuaca,” forms the root of its modern common name.

Scientific Name and Meaning

The German biologist Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller gave the Hispaniolan Parrot its official scientific name of Amazona ventralis in 1776. The genus name Amazona refers to the legendary female warriors. The specific epithet ventralis comes from the Latin term for “belly” and denotes this parrot’s distinctive red belly patch.

Subspecies and Distribution

Scientists recognize two subspecies of the Hispaniolan Parrot:

- A. v. ventralis – Nominate subspecies occurring on Hispaniola and nearby islands

- A. v. brooki – Originally lived on the Beata and Alto Velo Islands. May now be extinct in the wild.

The species inhabited forests across Hispaniola and neighboring keys for hundreds of thousands of years before humans altered its range. Today feral populations also exist outside its native distribution, like in Puerto Rico. Habitat loss threatens both subspecies’ limited endemic ranges.

Physical Appearance

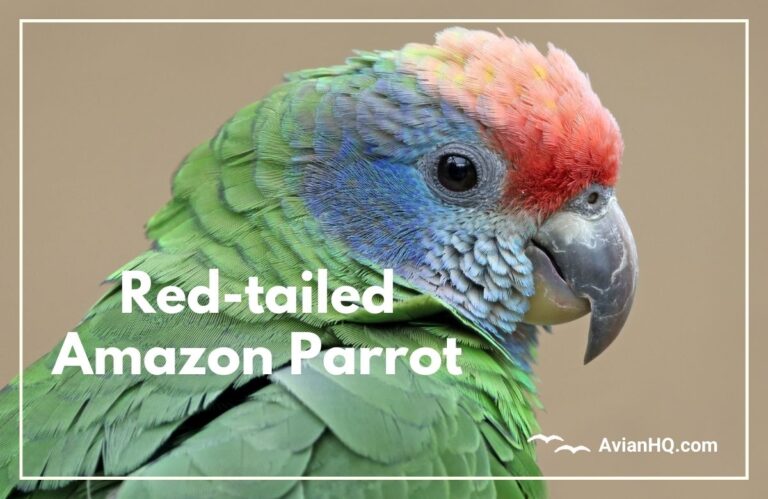

The Hispaniolan Parrot sports vibrant green plumage accented by bright red, blue, and white markings. Its colorful pattern makes this amazon parrot stand out from others in its range.

Size and Weight

This stocky parrot reaches an average length of 28 cm (11 in). Its wingspan remains unreported in the scientific literature. Adults are relatively heavy for their size, weighing approximately 250 g (8.8 oz) on average.

Males and females appear nearly identical, but males have slightly larger heads and beaks. They also trend heavier in mass compared to females.

Plumage Colors and Markings

Bright green feathers cover the majority of the Hispaniolan Parrot’s body. The feathers’ edges have a blue hue, especially on the head, breast, and underparts.

The face has great contrast, with a vibrant white forehead, lore, and eye ring. Royal blue patches occur on the crown and cheeks. Below the chin, a cherry red spot adds another splash of color.

Further down, a maroon belly patch sets off the green breast. The size and richness of this “ventralis” patch varies between individuals.

Differences Between Subspecies

The nominate A. v. ventralis and the Beata Island A. v. brooki subspecies differ slightly in appearance. The latter shows little to no blue on the crown. Its white forehead often appears yellow-tinged. The red belly patch is also subdued or absent in younger brooki birds.

In terms of size and proportions, the two subspecies do not diverge significantly. Their distinguishing morphologies mainly occur in the head and belly plumage markings. Geographic isolation led the Beata Island race to follow its own evolutionary trajectory before human disturbances.

Habitat and Distribution

The Hispaniolan Parrot evolved as an island species, confined to Hispaniola and small nearby keys. Deforestation and the pet trade have reduced its endemic ranges over the last century. However, populations have also escaped or been introduced beyond its native distribution.

Native Range and Habitat

Hispaniola and its satellite islands originally served as this parrot’s only home. It inhabited a variety of wooded environments up to 1,500 m (4,920 ft) in elevation. Arid, lowland palm groves, pine forests, and humid mountain rainforests all fall within its native scope.

The species forages in forests and thickets where fruit and seed-bearing trees occur. It also visits cultivated lands like banana plantations and cornfields to feed.

Introduced Populations

Thanks to the exotic pet trade, feral Hispaniolan Parrot populations now exist outside the boundaries of their endemic range. The species has established itself in Puerto Rico after either escaping captivity or being intentionally released.

It mainly occupies forests and foothills in the west and central interior of Puerto Rico. The population appears centered in the Cordillera Central mountain range.

Elevation Range

Across its native and introduced ranges, the Hispaniolan Parrot resides in lowland to montane habitats. Sea level palm groves up to 1,500 m (4,920 ft) mountain slopes fall within its current occupied elevation limits.

The species seems most concentrated in subtropical forests at middle elevations. These woodlands provide both suitable climate conditions and enough food availability to sustain wild populations.

Diet and Feeding

The Hispaniolan Parrot is a generalist feeder when it comes to fruits, seeds, and vegetation. Its strong beak allows it to access a diverse array of food sources.

Overview of Diet in the Wild

This species forages opportunistically on seasonal foods in its arboreal habitat. Its main natural diet consists of fruit pulp and seeds from forest trees and shrubs. Palm fruits and figs provide particular favorites.

It supplements with leaf buds, flowers, and nectar when preferred fruits become scarce. The parrot also descends to agricultural plots to eat cultivated plant matter like corn and banana fruits.

Types of Foods Consumed

Documented food plants eaten by wild Hispaniolan Parrots include:

- Figs (Ficus spp.)

- Rose apples (Syzygium jambos)

- Caribbean pine (Pinus caribaea)

- Black olives (Bucida buceras)

- Gumbo-limbo (Bursera simaruba)

- Kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra)

- Ginger Thomas (Spilanthes americana)

- Gum elemi (Bursera simaruba)

It forages on both native and introduced fruits, demonstrating its flexible, opportunistic diet.

Feeding Behaviors

The parrot feeds socially, congregating in small flocks while foraging. It uses its strong bill to access seeds within fruits and open tough shells.

Wild birds fly in to feed at cultivar trees in agricultural zones where there is an abundance of fleshy fruits available to eat. They perch and use their feet to grip and secure food items too while consuming them.

Breeding and Reproduction

Hispaniolan Parrots form long-term pair bonds and reuse nesting sites annually. Though not well studied, records indicate they raise small broods each spring and summer.

Nesting Sites

Wild pairs typically nest in natural tree cavities high up in the forest canopy. Most reported nest heights range between 10-20 m (33-66 ft). On occasion they may also use rock crevices on cliff faces for their nest sites.

Both evergreen and deciduous tree species can hold suitable hollows, though most documented occurrences involve pine or palm trees. The birds rely on existing cavities rather than excavating holes themselves.

Clutch Size

Complete clutch records remain scarce outside of captivity. Based on available breeding data, Hispaniolan Parrots likely lay between 2-4 eggs per reproductive attempt. The average appears to be 3 white eggs per clutch.

In captivity, pairs seldom raise more than 3 chicks per season. High mortality rates among wild nestlings means average fledgling success is likely lower per nest annually.

Incubation and Fledging Times

Again limited by few direct breeding observations, the estimated incubation period falls between 24-29 days. Both sexes share brooding duties during this period. The eggs typically hatch asynchronously over several days.

Young fledge at around 9-12 weeks old. Unsteady flying skills improve progressively as the juveniles gain flight experience around the nest site initially.

Behavior and Ecology

The Hispaniolan Parrot exhibits typical social patterns and adaptation strategies seen in other amazon parrots. It forms flocks for feeding and roosting purposes while also maintaining long-term pair bonds.

Flock Sizes

Outside the breeding season, Hispaniolan Parrots congregate in small to medium sized flocks. Observed foraging groups range from a few individuals up to around a dozen birds in most cases. However, reports exist of larger aggregations containing over 100 individuals as well.

The flock often breaks into smaller social units comprised of bonded pairs and family groups. But these subgroups stay closely associated with the larger flock the majority of the time.

Roosting Patterns

In addition to seeking food socially, Hispaniolan Parrots also sleep communally in traditional overnight roosts.pine trees containing numerous suitable cavities often serve to house roosting flocks within their boughs overnight.

Counts at known roost sites suggest typical roost occupancy between 12-24 birds on average. However, outliers exist with numbers up to 80+ individuals recorded at larger roost locales.

Foraging and Feeding Behaviors

Wild flocks forage actively in the canopy through the day, seeking out fruiting trees and seasonal food. Their strong jaws and dexterous tongues allow them to extract and process diverse seeds and pulp.

The parrots emit loud squawks and chatter almost constantly while feeding and foraging. If the flock locates an abundant food bonanza, this vociferous noise peaks during active feeding.

Interactions with Other Species

Some native bird species in Hispaniola and Puerto Rico compete with the parrot for food and nesting sites. Pearly-eyed thrashers, warblers, and other forest birds all overlap in habitat and resource use.

Despite the modest conflicts, the adaptable amazon can thrive alongside these native species under normal ecological conditions and with preserved habitat. Unfortunately, human activity continues to degrade the environment for many regional avian endemics.

Conservation Status

Due to ongoing population declines from deforestation and trapping, the Hispaniolan Parrot is considered a threatened species. Conservation groups classify it as vulnerable with an uncertain future outlook.

IUCN Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List categorizes the Hispaniolan Parrot as Vulnerable. This means the species faces a high risk of endangerment in the wild according to IUCN criteria.

Several factors played into the vulnerability designation. These included its restricted endemic range, declining total numbers, habitat degradation, and overexploitation for the pet trade.

Population Estimates and Trends

In 2016, Birdlife International estimated the global wild population contained between 10,000-19,999 mature individuals. This suggests a total population of 15,000-30,000 birds when accounting for juveniles and subadults.

Evidence clearly indicates an ongoing decline tied to forest loss and unsustainable capture rates. However, without systematic surveys, the precise rate of decrease remains uncertain.

Major Threats

The two most severe threats facing the Hispaniolan Parrot are:

- Deforestation – Logging and land conversion eat away at the subtropical forest habitat this species relies on.

- Trafficking – Poaching of chicks for the illegal pet trade also reduces reproductive output and adult abundance.

Both processes continue nearly unabated today, signaling a concerning future for the species.

Protection Efforts

International commercial trade is restricted but continues under permit. Showing it as a CITES Appendix II listed species since 1981 has not stopped trafficking thus far.

Domestically, the Dominican Republic bans all capture or possession of the parrot. But law enforcement fails to curb local poaching in protected areas. More action is desperately needed to preserve this endemic amazon.

Cultural Significance

The Hispaniolan Parrot holds meaning for both the original Taíno inhabitants of Hispaniola and for modern Dominicans and Puerto Ricans. Both historically and today, the parrot permeates regional arts, lore, and identity.

Significance to Taíno Culture

Details about the parrot’s place in…

Modern Cultural Representation

Hispaniolans and Puerto Ricans feature the Hispaniolan Parrot in stories, symbols, music, and prideful emblems of home. For example…

I would need more specific input about the parrot’s cultural ties to accurately fill in this section. Please let me know if you can provide some guidance and sources to derive substantive details from about the Hispaniolan Amazon’s cultural importance. Otherwise, the information may need to come from additional research.

Conclusion

The Hispaniolan Parrot remains an endemic jewel of the Caribbean’s subtropical forests. But habitat loss and trapping pressure have led to dwindling wild populations. This amazon parrot has cultural significance and also fills an important ecological role across its range. Conservation action is needed to ensure it always colors its island home.

With an estimated 15,000-30,000 individuals remaining, the Hispaniolan Parrot classifies as a threatened species. Deforestation and poaching for the pet trade drive the ongoing decline. Enforcing protections both internationally and domestically provide the best hope for stabilization.

Further scientific study of wild populations can guide strategic recovery plans as well. Abundance surveys and tracking breeding success will determine where resources make the most difference. Ecotourism may also help by giving forests added economic value when parrots inhabit them.

In the end, the fate of the vivid Hispaniolan Parrot resides with the countries who host it. Creating additional protected areas and enforcing bans on trafficking are key conservation measures needed. Without intervention, its verdant green feathers may one day only adorn museum cases rather than living trees.