Lord Howe Parakeet (Cyanoramphus subflavescens)

You gaze up into the canopy of palms and dense rainforest vegetation, hoping to spot one of the rarest birds on the planet. There, amongst the leaves, you see a flash of brilliant green and yellow. It’s a Lord Howe Parakeet, soaring through its remote island home located 380 miles off Australia’s mainland coast.

Endemic to this lone volcanic isle only 6 miles wide, no more than 250 of these vibrant little parrots remain. Classified as critically endangered, they cling to survival due to extensive habitat loss. Yet still they brightness this tropical paradise like feathered gems with their dazzling hues.

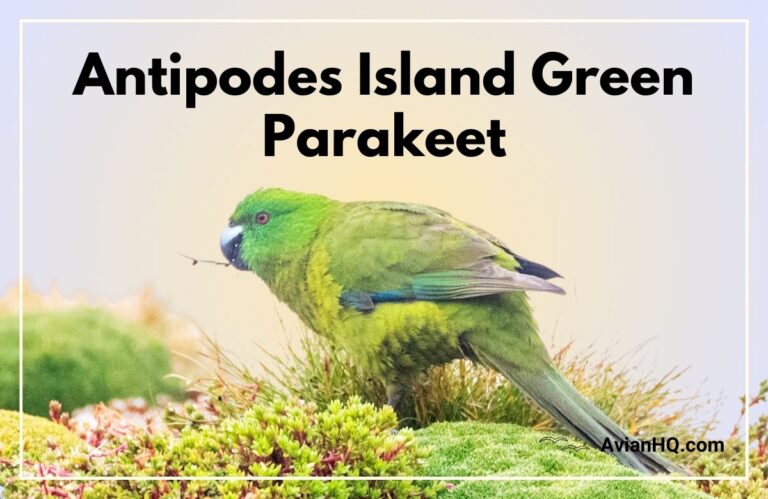

Measuring just 11 inches from head to tail, the Lord Howe Parakeet exhibits resplendent plumage. Brilliant green wings and back offset their golden yellow heads and breasts. With rounded tails and the characteristic curved beaks of parrots, these budgerigar-like creatures stand out against the palm fronds. Their verdant and gilded feathers once inspired the island’s nickname of “Paradise of Parakeets.”

But without proper conservation, you may never witness these Polynesian parrots again outside of history books. Urgent actions have been underway since the 1960s to prevent their extinction. From captive breeding initiatives to habitat restoration, reversing centuries of introduced predators and deforestation, there is hope on the horizon to save this natural treasure.

History and Taxonomy

The Lord Howe Parakeet remained unknown to early European explorers when they first encountered the island in 1788 aboard the HMS Supply. They failed to provide any record of the abundant parrots. It wasn’t until 1834 that naturalists visiting aboard the British warship HMS Challenger noted the bright green and yellow birds.

English zoologist George Robert Gray first scientifically described the species in 1859, classifying it as Platycercus subflavescens. Later renamed Cyanoramphus subflavescens, today it still bears this identification as its binomial nomenclature.

Belonging in the Psittaculidae family within the parrot superfamily, the Lord Howe Parakeet is a true parrot. Designated as a member of the Cyanoramphus genus, its closest cousins include the Antipodes Parakeet, Red-fronted Parakeet, and Three Kings Parakeet—all restricted to small islands around New Zealand averaging 15 to 30 miles wide.

Sharing traits like bright plumage and adaptation to island ecosystems, parakeets in the Cyanoramphus genus likely descended from mainland Australasian ancestors. At some point estimated within the last 2 million years, ancestral parrots dispersed to remote volcanic islands. Here they remained isolated with limited predation, evolving into the unique endemic species recognized today.

The establishment of captive breeding programs began In 1969 at the Sydney Royal Botanic Gardens and Australian National Wildlife Collection in Canberra after recognition these unique parakeets teetered at the edge of extinction. These efforts over subsequent decades eventually enabled small numbers to be reintroduced at Lord Howe Island, saving the Lord Howe Parakeet from vanishing forever into history.

Physical Appearance

Measuring 11 inches (28 cm) from head to tail, the Lord Howe Parakeet exudes a vivid brilliance. Weighing only 1.5-2 ounces (40-55 grams), its lightweight body enables effortless flight between palms.

Splashes of neon colors decorate its feathers. The forehead, checks, breast and abdomen glow bright yellow while emerald wings and back contrast dramatically. A few yellow and green feathers intermix between areas in a gradient pattern. Tail feathers display yellow tips.

Like most parrots, the Lord Howe Parakeet does not exhibit differences in plumage between males and females. Juveniles look nearly identical to adults as well aside from slightly duller versions of the vibrant coloration.

A few key physical traits differentiate the Lord Howe Parakeet from close Australian cousins. It possesses an overall smaller stature and shorter tail. The upper mandible of its signature curved parrot beak contains a distinct notch absent in related species.

Researchers hypothesize this unique beak feature may allow easier access to palm fruit kernels—an important part of the species diet. While feeding, the parakeet can wedge open seeds more readily to access the nutritious interior contents other parrots might struggle to unlock. This gave the Lord Howe a competitive edge on an island lacking sufficient resources to sustain too many bird species.

The parakeet’s bright spring green wings, thought to be an adaptation for camouflage amongst foliage instead of attracting mates, also set it apart. No matter the purpose, there’s no denying this little parrot’s beauty belongs alongside macaws and cockatoos as one of nature’s living rainbows.

Habitat and Distribution

The Lord Howe Parakeet evolved as an endemic species to remote Lord Howe Island—a solitary land mass located 380 miles (611 km) off Australia’s east coast in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand. Formed from volcanic eruptions more than 6 million years ago, this small tropical island spans only 6 miles wide by 2.5 miles long (9.7 km x 4 km).

Mountainous and lush from ample rainfall, Lord Howe vegetation primarily consists of dense rainforests, palm groves and woodlands dotted with banyan trees. Its mild subtropical climate stays near 70°F year-round (21°C) with average humidity at 75-80%. Within this limited world the Lord Howe Parakeet long flourished while most other bird species failed to take hold except petrels, rails, pigeons and songbirds like the endemic Lord Howe Golden Whistler.

Historically existing nowhere else but Lord Howe Island located halfway between Australia and New Zealand, the parakeet once inhabited nearly all forest and palm habitats across the full land area. But forest clearance and depredation of nests caused populations to dwindle until only 200-250 birds congregated in small areas of remaining palms by the 1960s. Conservation actions expanded restored habitats, enabling some increase again closer to 500 birds partially recovered in select areas of their former range. Reintroduction programs stand poised to boost populations and distribution wider still—a hopeful outcome after this parakeet narrowly escaped fading into extinction.

Diet and Feeding

The Lord Howe Parakeet holds the designation as the only completely herbivorous parrot species in the world. It does not consume any insects or meat like close relations. Instead, a key to its survival lies in the ability to derive sufficient nutrition from plant sources alone on an island lacking diverse food resources.

Frugivory represents the primary feeding mode, with its curved beak specially adapted to open tough palm fruits. The parakeet’s diet consists predominantly of palm tree kernels and nuts from the abundant native Kentia palms (Howea forsteriana). It swallows these whole to later access the meaty interiors.

The parakeet supplements palm nuts with nectar from various flowering shrubs and trees like banyans, lillipillis and shoebuttons. Pollen and ripe forest berries also occasionally get ingested. Rarely, if palm crops fail in drought years, the parakeet falls back on seed pods and green leaf shoots—but only feeds nestlings these suboptimal backup meals as a last resort since they provide inadequate nutrition.

To crack open the tough shells of palm nuts, the upper mandible of the Lord Howe Parakeet’s light green beak evolved a special notch near the tip not found in close Australian cousins. This enables easier access to the nutritious oil-rich kernels through prying action. They use their muscular tongues to manipulate and swallow the kernels, rarely dropping them thanks to uniquely structured throat muscles.

Feeding occurs most actively soon after sunrise when nuts mature overnight and sugars in nectar flow fastest. Late afternoon through dusk also provides prime foraging time on ripened fruits and arboreal flowers. The parakeet feeds either solo, in pairs or small familial flocks of 12 or less, congregating in palms and blossoming trees heavy with bounty.

Breeding and Reproduction

The Lord Howe Parakeet reaches sexual maturity by 18 months old. Monogamous breeding pairs mate for life. The breeding season falls between September and March yearly, coinciding with the spring and summer months on the island which sustains the most abundant food sources.

Elaborate mating displays take place as the pair strengthens their lifelong bond. The male parakeet exhibits courtship feeding, regurgitating palm nuts to the female accompanied by loud squawks, spreading wings and bobbing motions. If she accepts, the pair preens each other’s colorful feathers and may gently lock beaks. The female later solicits mating by positioning herself horizontally on a perch, ready to produce the season’s clutch.

Nest hollows get excavated high up in the decaying trunks of palm trees typically 15-30 feet (5-9 meters) above ground. Both the male and female parakeet use their curved beaks to meticulously dig out a round hole in the soft inner wood of the Kentia or Curly Palm over several weeks. Shredded bits of wood get cleared out creating a cozy cavity ready to cradle a clutch of eggs.

The typical clutch numbers only two or three small white eggs averaging .8 inches (2 cm) long. The female incubates them alone for around 21 days while the male gathers food and guards the nest site vigilantly. Upon hatching featherless and helpless, the hungry chicks get fed regurgitated fruit pulp by both parents constantly over 6-8 weeks until fledging from the nest. Most breeding pairs succeed in raising one chick annually.

Behavior and Ecology

The Lord Howe Parakeet leads primarily an arboreal existence, spending nearly its entire life amongst the rainforest canopy and palms where it roosts, forages and breeds. Seasons dictate much activity within this restricted realm.

Daily patterns adjust depending on weather, food resources and breeding duties. In peak summertime when nut crops flourish, most activity runs from dawn to mid morning then again late afternoon into dusk. Hot midday hours get spent quietly hidden amongst the fronds. Breeding season keeps bonded pairs busier sustaining demanding hatchlings from early morning well into evening with fewer breaks. Rainstorms prompt short periods of shelter seeking before returning promptly back to vital foraging tasks.

Roosting occurs in family units amongst dense clusters of Curly Palm fronds called crowns which offer shelter. Here the largely silent parakeet tucks its head behind wing to rest safely hidden above ground predators. High up in these lofty palms it also digs out nesting hollows.

The parakeet always occupies territory overlapping with native palms which provide the bulk of sustenance. Home ranges stretch up to 30 acres (12 hectares) depending on food scarcity. Within these zones only the mating pair freely roams while juvenile fledglings remain sheltered close nearby. Sizable flocks rarely congregate except at the most bountiful food sources in peak season, dispersing quickly back to defensive domains.

Few creatures pose dangers to this well concealed canopy forager outside of occasional aerial attacks by seabirds and raptors including owls and the native Lord Howe Island Peregrine Falcon. Defensive behavior consists mainly of fleeing rapidly deeper into vegetation cover. Its main survival strategy relies on camouflage and discretion. Successful adaptation to such an isolated habitat with so few competitors indeed served the Lord Howe Parakeet well for thousands of years—until human intervention disrupted the ecological balance.

Conservation Status

Centuries of blissful isolation kept the Lord Howe Parakeet thriving as one of the island’s most prolific endemics. But human activity soon tipped populations into dangerous decline toward extinction. Habitat destruction along with imported pests and disease decimated their numbers from abundant to critically endangered.

Following European discovery of Lord Howe in 1788, sailors and settlers unleashed goats, pigs and black rats by 1800. These invasive mammals devoured native vegetation, preventing forest regeneration. Black rats eagerly raided wildlife nests for eggs and chicks, including those of the defenseless parakeet unaccustomed to such predators. Whalers and fishermen also frequently poached the parrots for food. Deforestation then intensified from 1856 onward through burning and logging trees for agriculture, causing wholesale habitat loss. Stocks of the once common parakeet rapidly dwindled.

By 1923 surveys estimated less than 50 Lord Howe Parakeets clung to existence. Alarmed at their imperiled status, capture and export finally halted along with culling of goats by the 1930s. However the parakeet population continued declining further when in 1964 the deadly Ceratopyslla setosa bat flea introduced from Australia began spreading a pox-like virus. This severe disease erupts in open skin lesions often leaving afflicted birds blind, preventing proper feeding and eventually causing death. Soon only 20-35 parakeets remained, putting the species on the brink of extinction.

In response, the Lord Howe Island Board launched intensive recovery efforts still ongoing today. Select survivors got captured and quarantined for captive breeding to revive populations. Eradication of black rats, feral cats and illegal logging allowed palm and forest habitats to regenerate. A vaccine against the parakeet pox virus continues managing disease outbreaks. From the 1990s onward these persistent conservation actions facilitated the slow return of wild Lord Howe Parakeets with numbers now estimating around 320 adults. While still endangered, extinction got narrowly averted and hope renews populations still have potential to fully recover their island realm one day soon.

Cultural Significance

The very moniker “Lord Howe Island” pays homage to the flagship endemic parakeet residents early British mariners observed in abundance. Throughout the 1800s sailors and settlers viewed both the island and parakeets as exotic Polynesian treasures, referencing a “paradise of parakeets” in their accounts. Studies describe the species as highly valued historically both as colorful live specimens eagerly sought by collectors and as food. Their image came to symbolize island wildlife and the unique bioregion belonging neither to Australia or New Zealand by political boundaries yet an ecosystem unlike either.

As the avian emblem for this World Heritage Site, the Lord Howe Parakeet plays a special role in fostering pride and attention toward broader conservation goals to protect the fragile island habitat and its rare diversity of plants and animals. Since the parakeet came so dangerously close to extinction beginning in the 1960s, concerted recovery initiatives stand as a model of successful species and ecosystem preservation through control of invasives and disease, public education and captive breeding efforts. From school curriculum highlighting the parakeets to informative signage for tourists to sponsorship programs empowering locals to replant native vegetation, outreach continues engaging everyone to participate in healing ecological damage. Tour companies now lead birding excursions to see the vibrant parakeets in their palm forest home as a source of eco-tourism revenue benefitting residents.

While much works remains to restore stable wild populations and forest habitats, the Lord Howe Parakeet importantly shines as a hopeful victory and key motivator for ongoing conservation across the island that nearly lost one of its most iconic and beloved inhabitants. The extinction of this tiny parrot would have signified not only the loss of a beautiful and fascinating species, but also further degradation to the island’s fragile biodiversity and human connection to the environment. Its survival instead gives flight to the aspirations of all those fighting to preserve the special character and ecological heritage of the remote subtropical forests it calls home.

Conclusion

The vibrant green and yellow Lord Howe Parakeet stands as one of Earth’s most visually stunning birds, yet tragically as little as 300 of these Australian natives teeter on the brink of extinction. Restricted to its namesake remote volcanic island between Australia and New Zealand harboring at least 10 endemic plant and animal species found nowhere else, this petite parrot filled a special role in island ecology over millions of years as a seed spreader facilitating forest regeneration. Driven devastatingly close to extinction by habitat destruction, uncontrolled predators and deadly disease outbreaks in just decades, the beloved parakeet also holds treasured status as the island’s flagship symbol for unique biodiversity.

Now the focus of intensive recovery efforts through captive breeding and release programs in restored protected habitat aimed at revival of wild populations, the Lord Howe Parakeet offers inspiration and cautious optimism in the global challenges of species conservation. From students studying its importance as an essential part of the delicate island ecosystem to tourists appreciating its flash of green and gold winging over palm groves, this Polynesian parrot became a motivator for forest regeneration and invasive mammal eradication to heal the island from centuries of devastation by human activity. The continued survival of the amazing Lord Howe Parakeet in its island paradise depends now on persistent environmental stewardship valuing all facets of its rare endemic biodiversity worth treasuring for generations to come.