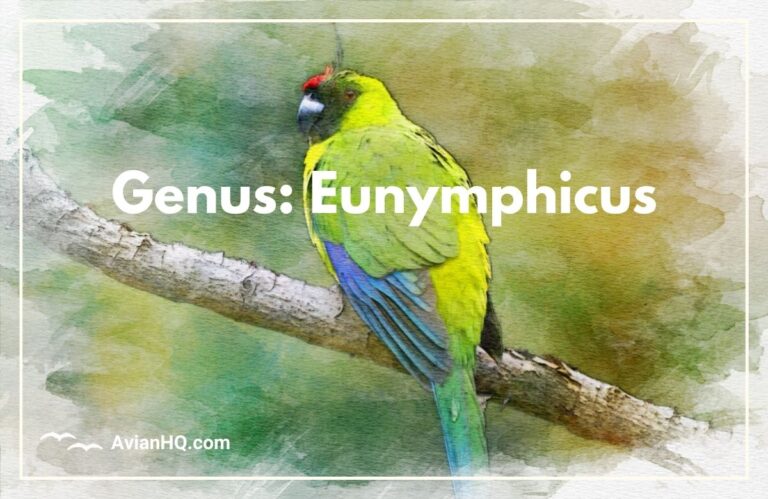

Horned Parakeet (Eunymphicus cornutus)

You spot a flash of green and orange flying through the canopy. It lands on a branch, cocking its head as it examines a fruit. But then you notice the unique feature that gives this parakeet its name—two feathered horns sprouting from its forehead!

You’ve spotted the rare horned parakeet, found only on the Pacific island of New Caledonia. Approximately 30 centimeters (12 inches) from head to tail, it sports vibrant plumage in shades of green, blue, orange and black on its wings and back. The male and female look similar, except the female’s horns and beak lack the dramatic orange coloration.

These colorful parrots fill an important niche in the island’s forests. They play a key role in seed dispersal and pollination as they forage for fruit and nectar. Their unique adaptations like strong beaks for breaking into tough fruit or wings tailored for quick maneuvering through branches help them thrive.

But today, only an estimated 1000 horned parakeets survive on New Caledonia. This puts them on endangered species lists globally. Much of their original habitat has been lost and competition from invasive species impacts their ability to breed and feed. Plus, their extremely limited range on one island makes them vulnerable. Conservation actions to restore forests and control predators aim to secure the future for these rare “unicorn birds” of the parrot family.

The horned parakeet offers a window into specialized island evolution. We’ll unravel more of their mysterious past, explore how their bodies have adapted, and learn why protecting these extraordinary feathered icons matters.

History and Taxonomy

The first known European description of the horned parakeet came in 1913 from the French zoologist Jean Roux. His account in the Bulletin de la Société zoologique de France documented the parakeet’s distinctive horns and named it Eunymphicus cornutus, meaning “well-horned” in Latin.

For decades, the species puzzled scientists. Its striking traits didn’t fit neatly into established parakeet genera. At one point, it was categorized as the sole member of the monotypic genus Eunymphicus. But today most experts classify it back within the larger parakeet genus of Cyanoramphus, despite its many unique adaptations.

Beyond written accounts, we have physical evidence of the horned parakeet’s existence going back over 1,000 years. Archaeological digs have uncovered horned parakeet feathers and bone fragments interred with native Kanak tribal members—suggesting an ancient cultural significance. Studies of mitochondrial DNA trace the horned parakeet’s ancestral line back to parakeet species in New Zealand. But it’s still the sole parakeet variety living on New Caledonia today.

Physical Appearance

The horned parakeet sports a brightly-colored coat of feathers from head to tail. Its main plumage consists of green wings and back feathers, a blue-streaked head and thighs, as well as orange and black accents on the tail and wingtips.

One of its most distinctive features lies on the forehead—two long feathers ending in caruncles that resemble horns up to 2 inches (5 cm) in length. These feather “horns” protrude vertically from above the eyes. Males develop larger and brighter orange-red horns and beaks starting in their second year. Females retain mostly black horns and beaks.

In body size, these parakeets reach approximately 12 inches (30 cm) tall on average and weigh 100 grams (3.5 oz). Their wingspan stretches around 8 inches (20 cm). Sturdy grey feet with zygodactyl toes (two facing forward, two backward) allow them to tightly grip branches. Short, hooked black beaks help crack hard nuts and fruits.

Molting of feathers occurs once per year after breeding season ends. Their lifespan in the wild remains uncertain but may reach over 30 years based on records of captive horned parakeets. Compared to related parrot species, they have excellent vision including good color detection even in low light conditions.

Habitat and Distribution

The horned parakeet resides only on the tropical Pacific island of New Caledonia, located east of Australia. This overseas territory of France harbors rare and endemic flora and fauna thanks to its long isolation. New Caledonia spans approximately 15,500 square miles (40,000 sq km) in size.

These colorful parrots occupy several forest habitats across their narrow range. You can spot them frequenting mangrove stands along the coast, palms and shrubs along forest edges, as well as primary evergreen tropical forests in the mountainous interior that receive high rainfall.

In particular, aged, towering araucaria pines serve as important habitat. Horned parakeets use holes in old araucaria and palm trees for nesting. They also rely on intact forests which provide the variety of native trees, vines, and flowers that make up their diverse diet year-round.

Territorial range sizes remain unconfirmed but likely fall between 10 to 30 acres (4 to 12 hectares) per mating pair or small flock. Generally shy and elusive, sightings often involve hearing them before seeing a quick-moving flash of green through thick foliage. But their signature raucous squawks will give away horned parakeets gathering at choice feeding or roosting spots.

Diet and Feeding

The horned parakeet is specialized to take advantage of fruit and nut food resources available in New Caledonia’s forests throughout the year. Classified among the Australasian parakeets within the true parrot superfamily, they share key adaptations for herbivory like strong beaks for breaking into hard-shelled foods.

You’ll observe these agile parrots foraging in the treetops for various native seeds, fruits, berries, and flowers. Favored foods include figs, mangoes, guavas, palms, laurels, and rose apples. Their sturdy beaks crack into the tough exteriors of nuts like macadamia nuts. Nectar and pollen also supplement the diet.

Foraging takes place most actively in early mornings and late afternoons in small flocks. The birds rely on scattered food sources which requires them to cover more territory daily. An average distance traveled during feeding may reach up to 18 miles (30 km) per day.

As they crack open fruits and nuts, bits of flesh and seed casings fall to the rainforest floor. This helps disperse the seeds of native vegetation in a role that benefits Caledonia’s whole ecosystem. Studies show nuts handled by parrots like macadamias germinate faster thanks to the seed coat perforations. The horned parakeet perfectly fills its fruit, nut and nectar eating niche on the island.

Breeding and Reproduction

The breeding season for horned parakeets falls between September through December, coinciding with peak fruit and seed resource availability. Courtship starts as early as March when breeding pairs isolate themselves within a defended nesting territory.

Both sexes reach sexual maturity at age three. Monogamous pairs may stay bonded for life, revisiting and defending the same nest site annually. But finding healthy breeding partners proves challenging when so few birds remain, making successful mating difficulty.

Nests often consist of tree cavities naturally hollowed out over time within heavy branches or trunks. Favorite nest trees include old araucaria pines, palm stubs, or mangroves that offer holes protected from predators. The female scrapes bark, debris and bird droppings to further hollow out the inside, often with help from her male partner.

A typical clutch contains three to four eggs which the female alone incubates over 24 days. The altricial young hatch with closed eyes and no feathers, needing extensive parental care. After another 50+ days for fledging, the young leave the nest but still depend on their parents into early winter. Reproductive success remains quite low, with less than a third of hatchlings surviving their first year. Expanding breeding sites offers a conservation priority.

Behavior and Ecology

Horned parakeets exhibit a social, monogamous mating strategy centered around defending nest sites and foraging territories. Mated pairs isolate themselves through most of the year except for small flocks that may congregate briefly at abundant food sources.

You can often hear flocks before catching a glimpse of them as they give loud, raucous squawks and screams. These vocalizations help maintain contact and signal alerts. Their calls carry distinct regional dialects across different forest areas—enabling researchers to track horned parakeet populations.

In flight, look for their fast, direct path on rounded wings alternating rapid flapping with short glides. Strong claws and a balancing tail adapt them for climbing and clinging easily in treetops. They spend most of their time off the forest floor, descending only for drinking water.

Compared to other parrot species, the horned parakeet fills its frugivorous niche with minimal niche overlap thanks to specialized feeding on certain fruits, seeds and nectars. But they still face competition from some native birds like imperial pigeons. Introduced deer, pigs, and cockatoos also degraded critical feeding and nesting resources. Protecting sensitive araucaria and rainforest habitat benefits all endemic species.

Conservation Status

The limited range and small population of horned parakeets have brought substantial conservation concerns. As few as 1,000 birds remain in the wild according to the latest estimates. Loss of old growth rainforest habitat poses one major threat.

Predation risks also increased after non-native predators like rats or feral cats were introduced to the island. With no native ground predators, parakeets nesting in tree cavities evolved no defenses. Monitoring programs now track population densities while habitat restoration projects expand protected forests.

The IUCN Red List categorizes the horned parakeet as Endangered based on its dramatically declining numbers. In 1981, the New Caledonia government listed them as a fully protected species. International commercial trade became banned under CITES Appendix 1 to combat poaching for the pet trade.

In captive breeding centers, over 100 horned parakeets live on display or in managed breeding colonies. These backup populations serve as an “insurance” against extinction. But experts aim to reintroduce captive-bred birds to bolster wild groups and genetic diversity. Saving New Caledonia’s extraordinary horned parakeet requires active habitat conservation combining policy initiatives with public support.

Cultural Significance

The horned parakeet holds a special place in the indigenous Kanak culture and mythology of New Caledonia. Traditional legends portray the parakeet as a protective spirit. Its horns earned it the nicknames “chief-of-chiefs” or the “bird that commands the Kago” (forest spirits).

Local tribes believed horned parakeet feathers carried magical powers to provide strength, health and good fortune. Chiefs adorned elaborate headdresses, staffs and clothing with the rare feathers. This cultural significance shows up in ancient burial sites where horned parakeet remains were found buried alongside human tribal members as long ago as 1,000 AD.

Today, the bird remains an icon for the Kanaks. Stylized images of the horned parakeet appear extensively in local artwork, textiles, carvings, and symbolism. As New Caledonia contends with balancing mining, logging and development projects with habitat protection, conservation groups adopt the parakeet as the face of environmental campaigns.

Eco-tourists travel from around the world in the hopes of sighting this exotic “unicorn bird” in Grove Creek and Riviere Bleu Provincial Park where guided tours operate. More accessible captive specimens never fail to enchant visitors to Noumea’s Tjibaou Cultural Center or the Botanical Gardens zoo exhibit. Safeguarding this avian emblem remains key to preserving New Caledonian natural and cultural heritage.

Conclusion

The rare horned parakeet offers a window into specialized island evolution. As one of the most distinctive members of the parrot order, this tropical “unicorn bird” still puzzles scientists with its mix of traits not found together in related species. Weighing little more than 3 ounces yet sporting a 12 inch frame, vibrant plumage, and signature feathered horns, it cuts a visually stunning profile.

But beyond its beauty, the horned parakeet fills an indispensible ecological role. As New Caledonia’s sole surviving parakeet, this fruit, nut and nectar feeding specialist facilitates seed dispersal and forest regeneration across its limited island habitat through a time-honed co-evolution with native vegetation.

Now endangered by extensive habitat loss as well as competition and predation from invasive species, intensive conservation efforts in recent decades aim to boost chances of survival. Habitat restoration projects, captive breeding/release programs, policy protections, and public engagement offer hope if enacted to sufficient degree. The outlook remains uncertain for these forest-dependent parrots. But losing the horned parakeet would mean far more than just the extinction of another rare bird—it would rob New Caledonia of an iconic living emblem intertwined with its natural and cultural heritage.