Cape Parrot (Poicephalus robustus)

As you gaze up into the canopy of South Africa’s lush Afromontane forests, you may catch a glimpse of vibrant green feathers and hear the raucous calls of the Cape Parrot (also known as the Levaillant’s Parrot). This striking bird is endemic to these forests, relying on ancient yellowwood trees to survive.

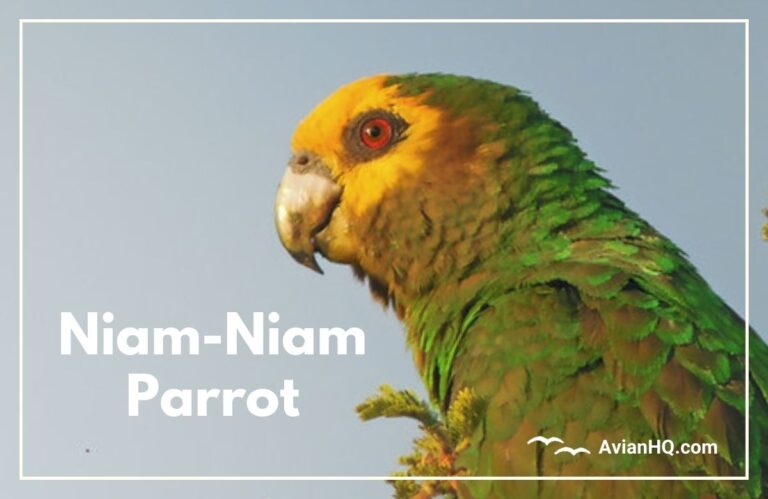

With a body length of 13-14 inches (34-36 cm) and weighing 9-14 ounces (260-410 grams), the Cape Parrot is a moderately large bird. Its bright green plumage and red thighs make it stand out against the forest vegetation. The Cape Parrot’s extremely large gray bill gives it the strength to crack open hard nuts and seeds.

You’ll notice significant variety in the plumage between individuals. Females sport a reddish-orange forehead patch, while juveniles show more pink on the head before attaining the red shoulders and thighs of mature adults.

These forests the Cape Parrot inhabits occur in a series of small patches near South Africa’s southern and eastern coasts. The largest populations are found in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. Sadly, extensive habitat destruction has led IUCN to classify the Cape Parrot as Endangered. Best estimates suggest only 1,000-1,500 exist in the wild.

In this article, you’ll learn all about the natural history, physical appearance, habitat, diet, reproduction, behavior, conservation status, and cultural significance of the Cape Parrot. Understanding this rare and intriguing bird can help support crucial protection efforts to ensure it’s survival into the future.

History and Taxonomy

The Cape Parrot’s scientific journey began when English ornithologist John Latham first described the species in 1781, referring to it as the “robust parrot.” A few years later in 1788, German naturalist Johann Gmelin named it Psittacus robustus, with the species name derived from the Latin word for “strong.”

For years, the Cape Parrot was considered a subspecies of the similar Brown-necked Parrot (Poicephalus fuscicollis). However, a detailed genetic analysis published in 2015 confirmed Cape Parrots as genetically distinct, having likely diverged some 2-3 million years ago during fluctuations between forest and grassland habitats in southern Africa.

Today, the Cape Parrot remains the only recognized species within the genus Poicephalus found exclusively in South Africa. No differentiated subspecies are known to exist. The genus name Poicephalus comes from the Greek words translating to “grey head,” an apt description for these parrots.

So while Cape Parrots have a relatively short documented taxonomic history compared to many other birds, the scientific community now universally recognizes these green birds as a valid endemic species crucial to South Africa’s natural heritage. Sadly, this distinction occurred alongside growing evidence of the species’ endangered conservation status.

Physical Appearance

The Cape Parrot is a stocky bird measuring 13-14 inches (34-36 cm) long. They are one of the larger members of the parrot family found in South Africa, with a weight range of 9-14 ounces (260-410 grams).

Their plumage consists of an olive green head, dark green back and wings, green underparts with a bluish tint, bright orange thighs, and a brownish-black tail. The forehead and crown of mature females takes on a reddish-orange hue.

As juveniles, Cape Parrots have a more pinkish forehead patch that darkens towards orange as they molt into mature plumage over 4-5 years. Their striking looks are finished off with ivory-colored bills and brown eyes.

There is significant variety observed between individuals, particularly in the extent of orange feathers on the head and wings. The blue tint on the underparts also ranges from darker teal to pale sky blue.

In flight, the contrast between the Cape Parrot’s green wings and orange thighs makes them stand out. Their slightly rounded tail and broad wings provide agile maneuverability within forest canopies.

Habitat and Distribution

The Cape Parrot is endemic to the Afromontane forests of South Africa’s southern coast. This habitat occurs in scattered patches spanning elevations from sea level up to 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) in some inland regions.

These forests are dominated by yellowwood trees that the parrots rely on for food and nesting sites. Three yellowwood species – Podocarpus latifolius, P. falcatus, and P. henkelii – are particularly important.

Cape Parrot populations are concentrated in two core geographic areas:

- The Amatole Mountains of the Eastern Cape Province, extending east to the Mthatha Escarpment and Pondoland

- The southern KwaZulu-Natal midlands from the coastal escarpment inland to Karkloof near Pietermaritzburg

A tiny isolated population of around 30 birds exists over 370 miles (600 km) north in Limpopo Province as well.

Sadly, the availability of Afromontane forest habitat has declined significantly in recent decades. Logging, land clearing, and urbanization have caused fragmentation, reducing the Cape Parrot’s range. Protecting remaining forest areas is crucial for the species’ survival.

Diet and Feeding

The Cape Parrot is specialized to feed on the nutritious fruits and seeds of yellowwood trees within it’s forest habitat. Their large powerful bills allow them to access the energy-rich kernels inside tough pods.

During times of yellowwood fruit abundance, Cape Parrots will gorge themselves to store fat reserves. However, they also supplement their diet with other fruits, berries, nuts, and seeds. Documented supplemental foods include:

- Acacia pods

- Plums

- Cherries

- Pecans

- Walnuts

- Oak acorns

- Sycamore figs

Cape Parrots use their hooked upper bill tip to peel back and shred softer fruits. For harder nuts and seeds requiring more brute force, the parrots will grasp them firmly with their feet and crack them open using the full leverage of their head, neck, and bill.

Foraging occurs high in the forest canopy, generally at heights above 33 feet (10 meters). Cape Parrots will attack a fruiting or nut-bearing tree in a flock, aggressively seeking the choicest ripened foods.

Breeding and Reproduction

The breeding season for Cape Parrots extends from August through February in South Africa’s summer. Courtship displays can be observed during this time as pairs strengthen their bond.

Cape Parrots nest in the hollows of large yellowwoods, often at great heights nearing the tops of the tallest trees. The female typically lays between 2-5 white eggs on a lining of decayed wood.

Incubation lasts 28-30 days before the helpless chicks hatch. Both parents share brooding and feeding responsibilities to allow each other intervals to forage. A few weeks after hatching, the chicks grow extensive downy feathers.

The chicks fledge at 9-12 weeks old, taking their first flights from their high nest to nearby branches. They continue relying on their parents for another couple months as they build flight strength and foraging skills.

Juveniles reach sexual maturity and begin breeding at around 5 years of age. Cape Parrots are believed to form long-term monogamous pairs that may last for life, unless a mate dies. In that case, the surviving parrot will seek out a new partner.

Behavior and Ecology

Cape Parrots exhibit highly social behaviors, foraging, roosting, and nesting in noisy flocks. These groups often contain 20-30 birds but can number over 100 at prime food sources.

Their loud squawking calls can be heard from afar as they commute between feeding and roosting sites. Cape Parrots settle in for the night in cavities of tall trees, often lining them with leaves and bark.

In flight, these parrots are highly agile, using rapid wingbeats interspersed with short glides to weave through the dense yellowwood branches. Their strong bite force allows them to hold firmly onto swaying perches.

Cape Parrots bathe frequently by lying down in shallow water and flapping their wings. This maintenance behavior helps condition their feathers for efficient flight.

When kept in captivity, Cape Parrots readily mimic human vocalizations and can be taught a variety of words and tricks. However, they may show aggressive tendencies towards other pets or unfamiliar people. Frequent positive interactions help socialize these birds.

Conservation Status

The Cape Parrot is classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List, and has been a focal species for conservation concern since the 1980s when extensive habitat loss accelerated.

From an estimated historical population of 10,000-15,000 Cape Parrots before widespread deforestation, current best estimates indicate between 1,000-1,500 remaining in the wild. These numbers come from annual census counts conducted by volunteers.

Over 300 Cape Parrots also reside in captive breeding facilities or wildlife sanctuaries, but attempts at reintroduction into the wild have so far been unsuccessful. Their survival depends on habitat protection.

The main threats facing this species include:

- Logging of ancient yellowwood trees for timber

- Forest clearing and fragmentation for agriculture

- The illegal pet trade – nest poaching remains an issue

- Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease (PBFD), an often fatal viral illness in parrots

Conservation actions in place aim to curb further habitat losses while restoring degraded areas through yellowwood reforestation projects. Nest boxes have also helped boost reproductive rates.

In addition, Cape Parrots are protected under CITES Appendix II, strictly regulating their international trade. Within South Africa, it is illegal to capture or own Cape Parrots without permits.

Conclusion

The vibrant green Cape Parrot remains a symbol of South Africa’s Afromontane forests – a unique ecosystem that has suffered devastating losses. As one of the region’s most endangered bird species, the fate of the Cape Parrot is inexorably tied to our ability to reverse those losses.

While robust and adaptable by nature, these parrots cannot withstand ongoing habitat destruction and fragmentation. Their specialized ecology evolves over millennia around mature yellowwood forests is struggling to keep pace.

Yet there is hope in the passion shown by the conservationists, researchers, and enthusiasts working diligently to preserve these last Edens for the Cape Parrot. Public education, legal protections, and habitat restoration collectively can chart a better future for the species if ramped up to match the scale of the crisis.

The next time you find yourself hiking through a patch of Afromontane forest and hear a raucous chorus erupt overhead, look up. With some luck, you’ll witness the Cape Parrot’s dazzling green, orange, and gray plumage amidst the dappled canopy. It’s a sight to inspire action on their behalf.