Red-crowned Parakeet (Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae)

As you gaze out over the lush green forests of New Zealand, a flash of crimson catches your eye. A small parrot with a bright red crown of feathers bobs through the canopy, its wings an iridescent green. You’re catching a glimpse of New Zealand’s only endemic parakeet species – the beautiful Red-crowned Parakeet.

About 30 centimeters (12 inches) from beak to tail, the Red-crowned Parakeet is a mid-sized parrot brightening up native forests from the Far North region to Stewart Island with its vibrant colors. Its scientific name, Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae, comes from Greek and Latin roots meaning “New Zealand blue-yellow bill.” But one look at the feathers on top of its head, and you’ll see where this little parakeet gets its common English name.

Once found throughout both main islands of New Zealand, loss of habitat now restricts remaining Red-crowned Parakeet populations to reserve lands and offshore islands. However, recent releases onto predator-free islands and mainland sanctuaries offer hope for the future.

As we explore the natural history, physical appearance, habitat, and conservation outlook for this eye-catching parrot, we’ll uncover why protecting New Zealand’s only native parakeet species matters. Let’s start by tracing the history of how the Red-crowned Parakeet was first discovered by early European explorers to arrive on New Zealand’s shores.

History and Taxonomy

The first known European documentation of the Red-crowned Parakeet came from explorer Captain James Cook during his first voyage to New Zealand in 1769. Cook and his crew recorded sightings of small green parrots with red markings on their heads. Specimens were later collected by naturalist Sir Joseph Banks and officially classified in 1788 by English ornithologist John Latham, who gave the species its original scientific name of Psittacus novaezealandiae.

Over the next century, several ornithologists reclassified the Red-crowned Parakeet into different genera based on new insights from studying morphological features. Notable name changes occurred in 1854 under naturalist Jean Cabanis’s designation of Platycercus novaezelandiae, and again in 1891 by renowned English zoologist Walter Buller with the naming of Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae.

This last scientific name change by Buller endures to the present day. The genus Cyanoramphus denotes the blue and yellow coloring in the wings and tail feathers, while the species epithet novaezelandiae signifies New Zealand as home to this parakeet species. No further taxonomic revisions have occurred since Buller’s classification over 130 years ago.

So while Captain Cook and crew can be credited for the first western documentation of our crimson-crowned friend back in 1769, it took subsequent decades for scientists to arrive at the enduring scientific name for the Red-crowned Parakeet that remains in use today.

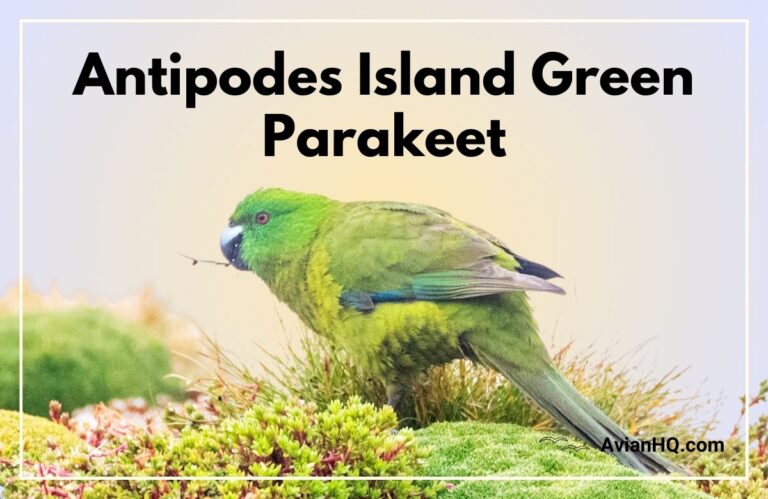

Physical Appearance

The most striking feature of the Red-crowned Parakeet is of course the vibrant red feathers topping its head, which give rise to its common name. These crimson crown feathers are unique among New Zealand’s parakeets.

In body size, Red-crowned Parakeets reach approximately 28 to 33 centimeters (11 to 13 inches) long on average from the tip of the beak to the end of the tail feathers. They are a mid-sized parrot similar in length to a Budgerigar, but somewhat slimmer in build. Average body mass ranges between 50 to 60 grams (1.8 to 2.1 ounces).

The base body color of adult birds is a bright grass green, covering the breast, wings, mantle, back region, and parts of the undertail. Some yellow-green edging occurs on the primary wing feathers. The lower belly transitions to a deep blue-violet hue. The pointed tail feathers display a mix of green, blue, black, and yellow banding. Female parakeets show a grayish tint to the green feathers on their wings and back.

Both sexes initially lack the red crown coloring as juveniles. The vibrant crimson head feathers instead emerge and intensify as young birds mature over their first year. At all stages, the stout beak maintains a bluish-gray hue with a lighter yellowish tip to the upper mandible – a distinguishing “blue-yellow bill” mark of the genus.

So when sighting a flash of green and red darting through New Zealand’s forests, you can confidently identify an adult Red-crowned Parakeet from its colorful namesake plumage.

Habitat and Distribution

Historically, Red-crowned Parakeets inhabited broadleaf and southern beech forests across New Zealand’s North and South Islands before human settlement. Deforestation from logging and land clearing for agriculture dramatically reduced their forest habitat over the past 800 years. Today, wild populations mainly occupy native forest fragments and reserves.

The northernmost strongholds lie within the vast Northland forests spanning the upper North Island. Scattered populations persist southward through coastal and lowland woodlands of the North Island’s eastern flank down to Wellington. On the South Island, most remaining wild Red-crowned Parakeets are restricted to pockets along the northwest Nelson/Marlborough region, including islands within the Marlborough Sounds.

Recent estimates put the total wild population at between 3,000 to 7,000 birds. However, their scattered distribution across 13 fragmented sites of native forest makes Red-crowned Parakeets more vulnerable to decline. Islands like Little Barrier in the Hauraki Gulf as well as predator-free Kapiti Island off Wellington support important protected populations as well.

Since 2020, conservation groups have also successfully translocated Red-crowned Parakeets to several mainland sanctuaries and small forested islands around New Zealand that previously lacked them. These habitat restoration efforts aim to reestablish additional genetically robust populations across a greater portion of the species’ original range over time through careful release and monitoring.

So from the upper Northland forests to the Marlborough Sounds and portions of New Zealand’s protected offshore islands, small dispersed bands of these crimson-crowned parakeets still frequent native bushlands their ancestors have called home for hundreds of years. Ongoing habitat protection and population restoration now seek to expand their safe forest habitat.

Diet and Feeding

As with most parakeets, Red-crowned Parakeets are primarily herbivorous, feeding on a variety of flowers, herbs, seeds, and fruits. Their typical diet consists of plant nectar, pollen, native seeds and berries, buds, blossoms, and leaf shoots.

Common native plants utilized for feeding include flax bushes, kowhai, fuchsia, tawa, and a number of coprosma and myrsine species. Red-crowned Parakeets use their pointed brush-tipped tongue to take advantage of flower nectaries. They have also adapted to take nectar from exotic flowers and fruits as well.

You’ll often observe these active foragers in small flocks of up to 20 to 30 birds, moving acrobatically through trees and overgrowth while feeding. The strongest populations on offshore islands like Little Barrier display more movement during mornings and afternoons between favored feeding trees and inland roosting sites.

On the North Island, favored food trees include pohutukawa, kohekohe and taraire. On the South Island, they will target wineberry, honeysuckle, fuchsia, flax and tree lucerne. No matter what native forest habitat they live in, a diversity of flowering and fruiting bush plants sustains populations of the Red-crowned Parakeet year-round.

So whether nipping buds high up in tall kauri trees or stretching to take nectar from flax flowers, Red-crowned Parakeets have adapted to extract nutrition from a wide breadth of native and endemic vegetation across New Zealand’s remaining forest fragments.

Breeding and Reproduction

The breeding season for Red-crowned Parakeets extends from November through February on the North Island and December through March on the South Island. The peak of egg laying occurs in December and January when abundant food sources aid breeding success.

As monogamous birds, they form close pairwise bonds, typically for life once paired off at age 2 to 3 years old. You’ll often see bonded pairs staying close together or preening each other’s feathers affectionately. Pairs vocalize to each other frequently with a contact call sounding like a shrill, rolling “keet” sound.

For nesting sites, Red-crowned Parakeets prefer either tree cavities from decay in large native trees or concealed forks amid dense vegetation like epiphytes or vines. Both sexes participate to build the nest structure, using small twigs, grasses, bark strips, and other plant material. Nest hollows measure approximately 8 centimeters (3 inches) wide and 23 centimeters (9 inches) deep on average.

The typical clutch size is 3 to 5 white eggs that the female broods for an incubation period lasting around 21 days. Once hatched, both parents share feeding responsibilities to deliver regurgitated plant material to nestlings. Chicks develop all juvenile feather coloring by age 8 weeks but need another month to graduate to flight.

Breeding productivity is lower for island populations, as nest predation can be high from native birds like kākā parrots. However mainland pens and restored sanctuary sites with predator control achieve higher nest success. From courtship rituals through to eventual fledging of chicks, proximity of mated pairs is crucial to each seasonal nesting cycle.

So the bonds formed between breeding Red-crowned Parakeets fuel continued nesting success. Care given to eggs and chicks also offers hope for boosting productivity to aid future population growth.

Behavior and Ecology

Red-crowned Parakeets exhibit very social behaviors, foraging and roosting in small flocks most times of year. The average group size ranges between 20 to 30 birds. Younger non-breeding birds may form larger flocks of up to 60 to feed.

Their flight pattern is swift and direct with rapid wing beats on initial take off. Soaring flight occurs across open spaces between forest patches or when moving dusk roosting sites. Their call is a rolling “keet” sound made in flight or when perched.

Roosting takes place in forest canopies during midday and more sheltered thickets overnight. Coastal populations may commute inland to roost. Bathing involves brief dips then vigorous shaking and preening plumage. Dust baths within loose soil also help ensure feather maintenance and skin cleansing.

As predominantly arboreal parakeets, most of their activity and life cycles take place high up or within the protection of tall trees and dense scrublands. Having adapted to coexist alongside other native New Zealand birds over centuries, Red-crowned Parakeets don’t compete strongly with other species.

Their chosen foods only partially overlap with nectar-feeding Tuis, Bellbirds, stitchbirds and Silvereyes. Nesting in tree holes even provides roosts for Blue Penguins on some offshore islands. Continued conservation to restore native habitats will aid the long term preservation of delicately balanced ecological relationships like these.

So whether calling loudly when approaching favorite feeding trees, taking brief baths at forest edge streams, or chattering excitedly upon returning to roosts, the Red-crowned Parakeet’s visibility and social bonds add vibrance to surviving stretches of New Zealand forests daily.

Conservation Status

Classified as “Nationally Vulnerable” under the New Zealand Threat Classification System, the preservation of the Red-crowned Parakeet faces several challenges.

Historical habitat loss from deforestation severely depleted populations over the past seven centuries. Remaining birds now mainly occupy small fragmented native bush areas totaling less than 10% of their original range. With an estimated 3,000 to 7,000 birds left in the wild, these small isolated groups are at higher risk.

Predation from invasive mammal species like rats, stoats and possums also lowered breeding success until protective sanctuaries could be established on predator-free islands. Avian malaria has had major impacts on populations in the past as well. Competition for nesting cavities with non-native species like starlings contributed to declines too.

However, successful transfers since 2020 to predator-free havens like Zealandia in Wellington, Cape Sanctuary on the Hawke’s Bay coast, and even the Auckland suburb of Ark in the Park now give reasons for optimism. Continued releases onto additional suitable predator-free islands and fenced sanctuary reserves should further boost overall population numbers and resilience over time.

Public education and community-led conservation initiatives also bolster protection efforts across remaining habitats. So while less than 5% of historic numbers exist, active management interventions provide genuine hope that New Zealand’s Red-crowned Parakeet populations can be preserved and expanded in secure locales long term.

Cultural Significance

The bright red crown feathers of New Zealand’s endemic parakeet feature prominently in titles and legends among some Māori iwi (tribes). The name “kākāriki” was used in these stories to refer specifically to the Red-crowned Parakeet.

According to tales of the Ngāi Tahu tribe, their ancestor Tū Te Rakiwhanoa journeyed from Hawkes Bay down to Kaikōura on New Zealand’s South Island pursued by a hostile war party. When the war party stumbled in the darkness, Tū Te Rakiwhanoa was said to have used the red feathers of the kākāriki to create a bright glow to aid their escape southward.

Other stories portray the red feathers being stained by blood during battle. Tribes would capture Red-crowned Parakeets and ceremonially use those blood-colored crown feathers to adorn battle helmets and other garments of chiefs. Variations on these themes emphasize the significance of the crimson feathers in tribal lore.

Today, the Red-crowned Parakeet remains prized in aviculture for its bright emerald green and ruby-red plumage. New Zealand’s unique endemic parakeet continues to hold an iconic status both culturally and environmentally as important campaigns now work to preserve its remaining native habitats.

So whether featuring in indigenous tales of clever escape exploits, or inspiring pride as a distinctly unique parrot only found in New Zealand forests, the crimson crowns of these small green parakeets stir the cultural imagination while underscoring modern efforts focused firmly on sustaining their populations.

Conclusion

The Red-crowned Parakeet holds a truly distinctive place as New Zealand’s only surviving endemic parakeet species. No other bird either locally or abroad matches its eye-catching mix of yellow-blue bill, emerald wings, rich violet underbelly, and of course, its namesake crimson crown feathers.

Weighing just 50 to 60 grams (1.8 to 2.1 ounces) and reaching 25 to 30 centimeters (10 to 12 inches) in length, these mid-sized parrots use brush-tipped tongues to feed on native forest flowers and fruits. Though now limited to scattered populations across remaining forest fragments, offshore islands and mainland sanctuary reserves offer real hope.

Active habitat restoration, transfers to predator-free refuges, and community conservation initiatives all combine to put New Zealand’s Red-crowned Parakeet on a brighter path after centuries of decline from deforestation and introduced predators. Continued public education and funding support remain vital for secure the futures of this special native taonga (treasure) and its forest ecosystem.

From its origins in Māori legend to its modern-day protected status, vibrant emerald green accented in scarlet means only one thing – the unique native Red-crowned Parakeet reigns over New Zealand forests once again thanks to dedicated efforts to preserve its ecological heritage.