Red-fronted Parrot or Jardine’s Parrot (Poicephalus gulielmi)

With their bright green bodies and flashs of red and orange, Red-fronted Parrots catch your eye. These mid-sized, long-tailed birds live in small flocks in the rainforests and woodlands of Africa. Their loud, chattering calls ring out as they swiftly fly above the forest canopy.

Red-fronted Parrots, also called Jardine’s Parrots, make engaging pets. They can learn to talk and delight owners with their playful personalities. However, trapping wild parrots for the pet trade may put pressure on wild populations already threatened by habitat loss.

These colorful parrots have a long history with humans. British naturalist Sir William Jardine first described the species in 1849 after his son brought one home from Africa. He named the parrot “Poicephalus gulielmi” in Latin after his son. Ever since, people have prized Red-fronted Parrots as pets and as a symbol of Africa’s diverse wildlife.

In the wild, Red-fronted Parrots live in small flocks and nest in tree holes. They use their curved black bills to crack open fruit, nuts and seeds. Though widespread, habitat loss causes their numbers to decline across their range. However, continued research and conservation efforts can help ensure Red-fronted Parrots continue to brighten Africa’s forests.

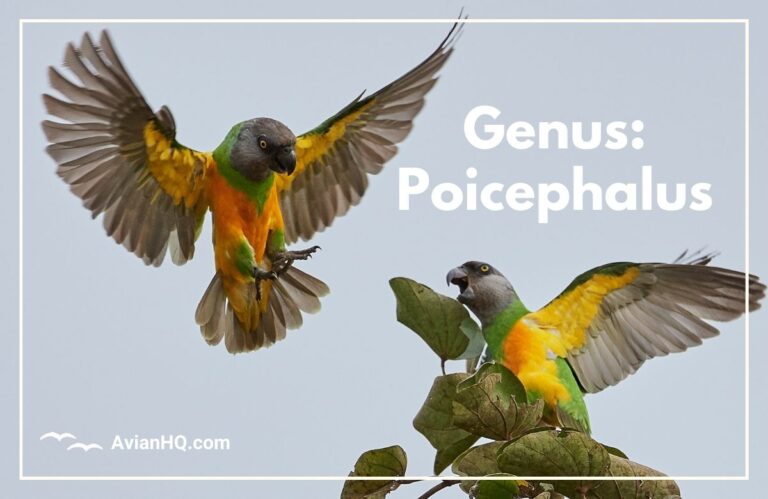

History and Taxonomy

The first written account of a Red-fronted Parrot came from Sir William Jardine, a Scottish naturalist living in the early 1800s. In 1849, Sir Jardine formally described and named the Red-fronted Parrot species after his son brought one home to Scotland following a long voyage at sea.

Sir Jardine named the parrot “Poicephalus gulielmi” with the species name gulielmi meaning “William’s” in Latin, after his son William. The parrot became known as Jardine’s Parrot in honor of the Jardine family’s discovery. Sir Jardine described the bright colors and loud vocalizations of this first captive Red-fronted Parrot, kept at the family estate.

Today, scientists recognize three subspecies of Red-fronted Parrots across Africa:

- Poicephalus gulielmi gulielmi: Found in the Congo River basin from Nigeria to Uganda and Rwanda. This subspecies has the red/orange markings on the head, wings, and thighs.

- Poicephalus gulielmi fantiensis: Native to coastal countries from Liberia to Ghana. Slightly smaller with an orange forecrown.

- Poicephalus gulielmi massaicus: Endemic to highland forests of Kenya and Tanzania. Has less extensive orange/red on forehead.

These subspecies differ slightly in size and coloration but share the same stocky green bodies, short tails, and loud calls associated with Red-fronted Parrots. Some experts also recognize hybrids between subspecies where their ranges overlap across Central Africa.

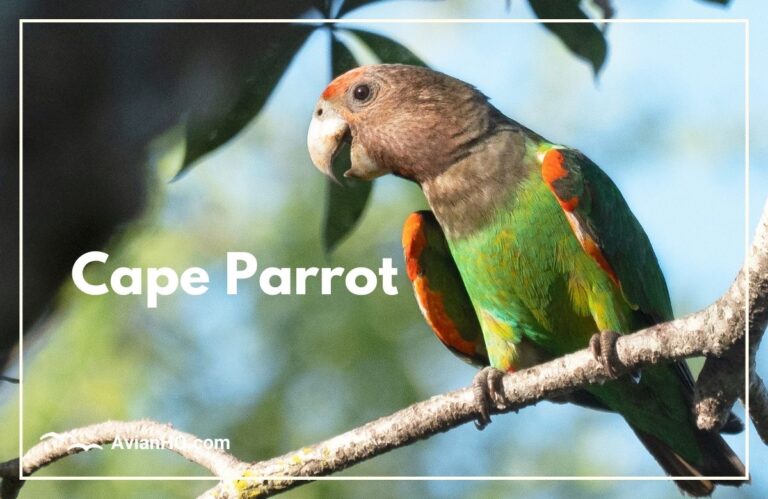

Physical Appearance

Red-fronted Parrots are stocky short-tailed parrots reaching about 11 inches (28 cm) long. Their wingspan stretches up to 12-14 inches (30-35 cm) across. These parrots are relatively heavy for their size, weighing 7-8 ounces (200-227 grams) on average.

Their plumage is primarily green, with a bright green head, back, chest, and underside. The rump and upper tail feathers are more yellow-green. The green wings show neat black barring and scalloping when closed.

Splashes of color come from orange-red patches on the forehead, thighs, and bend of the wings. The shade and extent of red varies based on the subspecies. For example, P. g. massaicus parrots have just an orange spot on the forehead.

Other key features include:

- Short blackish tail

- Horn-colored upper bill with a darker tip

- Bare white eye rings

- Red-orange eyes in adults

- Grey legs and feet

Male and female Red-fronted Parrots look nearly identical. Juveniles instead have mostly green and black plumage with dark grey beaks and brown eyes. Their colors intensify with each successive molt until reaching full adult colors by 2-4 years old.

Habitat and Distribution

Red-fronted Parrots live across the tropical rainforests and woodlands of Central and West Africa. Their native range stretches from southern Nigeria and Cameroon west to Ghana. Eastward, they occur from Kenya and Tanzania down into northern Angola.

These parrots reside in lowland tropical forests as well as highland mountain forests. In Kenya and Tanzania, they inhabit montane juniper and podocarpus forests at elevations from 1,800 feet (550 meters) up to their ceiling of 10,600 feet (3,250 meters). They also live in forests along the Congo River basin.

Red-fronted Parrots have adapted to secondary forests and agriculture areas. The P. g. fantiensis subspecies, for example, lives in coconut groves and gardens in coastal west African countries. Some populations in Angola forage in coffee plantations adjoining rainforest areas.

While overall widespread in Africa, Red-fronted Parrots face local declines across their range due to deforestation. However, they remain common in protected parks and reserves with intact forest habitat.

Beyond their native Africa range, a small introduced population of P. g. gulielmi parrots has become established on the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico. They likely escaped from the pet trade or were intentionally released. This non-native population is still quite small but may come into conflict with native Puerto Rican species.

Diet and Feeding

Red-fronted Parrots are opportunistic feeders that eat a varied diet. They consume a mix of seeds, fruits, berries, nuts, buds, and flowers. Their strong curved bill helps them crack into hard nuts and fruits other birds can’t access.

Some of their favorite wild foods include:

- Figs and wild olives

- Pods and seeds of juniper, cedar, and podocarpus trees

- Oil palm nuts

- Seeds of trees like the African tulip tree

- Berries and fruits like pomegranates and oranges

These parrots exhibit social feeding behaviors. Pairs or small flocks fly swiftly between night roosts and favorite feeding grounds, calling noisily to each other along the way. But once settled in the high canopy to eat, Red-fronted Parrots become quiet and can concentrate on foraging.

Their green plumage blends into foliage, helping camouflage them from below. They prefer to feed high in treetops that offer safety from predators. Flocks may also join mixed feeding assemblages with other African birds like pigeons, hornbills, and starlings.

In captivity, Red-fronted Parrots should be offered a nutritious prepared pellet diet. This can be supplemented with healthy table foods like cooked beans, vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and nuts. Key nutrients like calcium and vitamin A promote proper growth and development.

Breeding and Reproduction

Red-fronted Parrots reach breeding maturity between 2-7 years old. They form monogamous breeding pairs that may mate for life. The breeding season lasts from March to November across their range, with seasonal variation by region.

These parrots nest in tree cavities, occupying abandoned woodpecker holes or natural hollows. Nest holes are typically situated 3-10 meters (10-33 feet) high on a tree trunk. Both parents defend the nest site from predators and competitors.

Females lay clutches of 2-6 white eggs, with 3-4 eggs being most common. She incubates the eggs for 26-28 days while the male brings her food. Hatchlings are altricial, with closed eyes and just a sparse white down.

Both parents feed and care for the rapidly growing chicks. Young fledge at 9-11 weeks old and become independent soon after at 12 weeks old. Juveniles require another year or two to attain full adult colors in their plumage following successive molts.

In captivity, providing proper nest boxes helps red-fronts feel secure enough to breed. However breeding them can prove challenging, as they are prone to aggressive behavior between mates. Experienced aviculturalists may have better success with these sensitive parrots.

Behavior and Ecology

Red-fronted Parrots exhibit very social behaviors. They live in small flocks of up to 10 birds on average. Mixed flocks may congregate where food is abundant, such as fruiting trees.

These parrots show daily patterns in their activity and movements. They leave nighttime roost cavities at dawn and fly to favored feeding grounds, vocalizing loudly along the way. Their short, blunt wings provide rapid flight through the forest.

Some populations migrate locally on a daily basis, traversing nearly 40 miles between roosting and foraging areas. Others reside permanently near ample food sources. But all Red-fronted Parrots grow quiet once settled in treetops to feed.

Flocks display synchronized movements when alarmed. And pairs may perch close together to preen each other’s head and neck feathers as bonding behavior. Juveniles form crèches of young birds that socialize together.

Red-fronted Parrots typically associate with other bird species that share their habitat. Mixed flocks provide extra vigilance against predators like hawks and snakes. Some common associating species include pigeons, hornbills, starlings, and other parrot species.

Conservation Status

The IUCN Red List categorizes Red-fronted Parrots as Least Concern. However, many localized populations face threats and declining numbers across their range.

The global wild population is difficult to quantify but appears to be decreasing over time. These parrots vanish from areas where rapid deforestation removes critical feeding and nesting sites. Capture for the pet trade also pressures wild flocks despite legal protections.

Red-fronted Parrots occur in several protected areas across Central and West Africa. Well-managed parks and reserves could harbor key populations if enough intact forest remains. Expanding protected habitat and enforcing trade laws can prevent overexploitation.

All three subspecies of Red-fronted Parrot are listed under Appendix II of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. Appendix II listings regulate commercial trade to prevent impacts on wild populations. Permits are required for export and other transactions.

In addition, many African countries legally protect Red-fronted Parrots as wildlife. Killing, capturing, or collecting birds, eggs, or even feathers is prohibited without permits. However enforcement varies considerably across the continent.

Increased monitoring, anti-poaching efforts, and habitat conservation will give Red-fronted Parrot populations their best chances to rebound. Focusing conservation attention on this charismatic species can also benefit many other animals sharing it’s forest ecosystem.

Cultural Significance

The brightly colored and vocal Red-fronted Parrot holds a special place in human culture. Indigenous groups view the parrot as a symbolic or totem species across it’s African range. Many traditional African folktales feature the red-fronted parrot as a central character.

Europeans have prized these parrots as pets since at least the early 1800s when Sir William Jardine first described the species. Demand for Jardine’s Parrots in the pet trade continues today around the world. However, trapping wild parrots speeds up losses from African forests.

In parts of West Africa, red-fronted parrots are considered crop pests by some farmers. Flocks may steal cultivated fruits and grains, leading to conflict with agricultural communities. Changing attitudes through education could promote better coexistence.

Ecotourism potential also exists for the charismatic Red-fronted Parrot. Birdwatchers already seek out the species across it’s range. Wildlife tourism brings valuable foreign money to local economies in developing regions.

Going forward, the connections between Red-fronted Parrots and humans seem destined to continue. Ensuring sustainable use of it’s forest habitats can allow both people and parrots to share the same space.

Conclusion

The Red-fronted Parrot, or Jardine’s Parrot, is a colorful African species with strong ties to human culture. Since it’s scientific discovery nearly 175 years ago, these parrots have been traded worldwide as pets and featured in indigenous folklore.

While still widespread, Red-fronted Parrots suffer from habitat loss across their range. Their social habits and vocal nature endear them to people, yet trapping for the pet trade may negatively impact wild populations. Striking a balance allows both people and parrots to share the landscapes of Africa.

As forest habitats shrink, conservation concern for the Red-fronted Parrot becomes urgent. Expanding protected areas, enforcing trade regulations, and managing ecosystems will give wild flocks their best future outlook. With sound stewardship, these charismatic parrots can continue brightening Africa’s woodlands for generations to come.