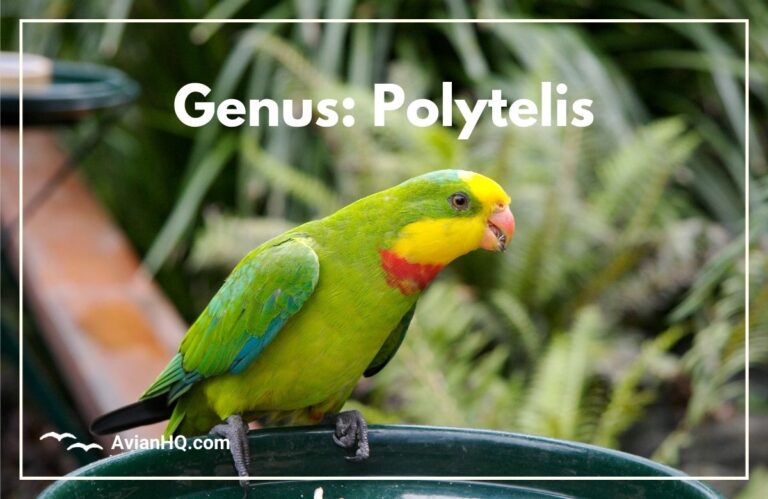

Regent Parrot (Polytelis anthopeplus)

As you traverse the eucalyptus forests and woodlands of inland southeastern Australia, keep an eye out overhead for a flash of brilliant yellow and blue-black wings. If you’re lucky, you’ll spot one of Australia’s most beautiful parrots in flight – the Regent Parrot.

“The male Regent Parrot’s vibrant plumage makes it one of Australia’s most visually striking parrot species.”

With it’s long tail tapering to a point and back-swept wings, the Regent Parrot cuts a slim, graceful figure as it flies. At around 16 inches (40 cm) from head to tail, it’s larger than a budgie but smaller than a cockatoo. Other notable features include:

- A prominent yellow shoulder patch on males

- Bright red patches in the wings visible against dark flight feathers

- A long, curved red or pink bill

The Regent Parrot shows some key differences between the sexes and ages. For example:

| Description | Plumage Colors |

|---|---|

| Adult Male | Mostly golden yellow with blue-black wings and tail |

| Adult Female | Olive-green head and underparts |

| Juvenile | Duller green plumage similar to adult female |

The species scientific name, Polytelis anthopeplus, offers some clues into the colorful appearance. Polytelis derives from Greek words meaning “many colored,” an apt description for the males’ striking contrasts. Anthopeplus also has Greek roots indicating “flower” and “cloak.”

While a beautiful sight in the wild, the Regent Parrot has also become popular in aviculture due to it’s beauty and pleasant nature when hand-raised. However, conservation efforts are vital for the endangered eastern subspecies in particular.

History and Taxonomy

The first known depictions of the Regent Parrot come from the early 1830s by English author and artist Edward Lear. In 1831, Lear published an illustration of a female specimen in his folio Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots, calling it “Palæornis anthopeplus.” The next year he included a painting of a male, given the name “Palæornis melanura.”

At the time, Lear did not specify where his parrot specimens originated from. It was not until 1912 that ornithologist Gregory Mathews stated they were native to New South Wales. Mathews also first described the separate southwest Australian population as a new taxon, “westralis.”

Today, the Regent Parrot is classified into two subspecies based on geographic separation:

- Polytelis anthopeplus anthopeplus – Southwest Australia

- Polytelis anthopeplus monarchoides – Southeast mainland Australia including southwest New South Wales, northwest Victoria, and southeast South Australia

The southwest Australian subspecies, P. a. anthopeplus, is more abundant within it’s range. However, the southeast population, P. a. monarchoides, is listed as Vulnerable under Australia’s EPBC Act and faces threats from habitat loss. Understanding these distinct subspecies and their conservation status is key for protecting the future of this uniquely Australian parrot.

The genus name Polytelis is derived from Greek words meaning “many-colored,” an accurate description of the brilliant male’s striking yellow and green plumage. The species name anthopeplus also has roots in Greek, combining “flower” and “cloak” or “robe” as a likely nod to the colorful feathers.

Physical Appearance

The Regent Parrot is a relatively slim, long-tailed parrot species. Full grown, they reach around 16 inches (40 cm) from the tip of the bill to the end of the tail. Body mass ranges between 5.3-7 ounces (150-200 grams).

Males and females show distinct sexual dimorphism in their plumage colors and markings:

Males

- Head, neck, underparts, rump, and shoulder patches are bright golden yellow

- Back and inner wing feathers are mixed green

- Outer wing flight feathers and long tail are shiny blue-black

- Red patches on wing coverts visible against darker wings in flight

- Bill is deep orange-red color

- Eyes are orange

Females

- Mostly green plumage on head, back, wings, and tail

- Underparts and shoulder patches dull yellowish green

- Smaller and duller red-pink patches on wings

- Tail broadly tipped with red-pink spots

- Bill, eyes, and legs less vibrant than male

Juveniles

Both male and female juveniles resemble adult females but are overall duller in their coloration before molting into mature plumage. Young males gain their full vibrant yellow and blue-black colors by 13-18 months old.

The two subspecies show subtle differences, mainly in the shades of green and yellow on the plumage. The southeast P.a. monarchoides tend to have more olive-green in the females’ head and underparts rather than bright yellow.

Habitat and Distribution

The Regent Parrot resides exclusively in Australia and is endemic to two primary regions – southwest Western Australia and southeastern South Australia/Victoria/New South Wales.

Southwest Australia

The P.a. anthopeplus subspecies is found across southern Western Australia. It’s range extends approximately:

- North to the Lake Moore district

- East to the eastern Goldfields and Balladonia district

- South to Israelite Bay

These parrots inhabit a variety of woodlands and open forests dominated by eucalyptus, especially:

- Salmon Gum (Eucalyptus salmonophloia)

- Gimlet (E. salubris)

- Red Morrell (E. longicornis)

They also occupy areas of mallee heath shrublands and chenopod/saltbush plains in the semi-arid interior.

Southeast Mainland

The P.a. monarchoides subspecies resides in the Murray Darling Basin region including:

- Southwest New South Wales

- Northwest Victoria

- Adjacent southeast corner of South Australia

Their habitat centers around River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) riparian woodlands and floodplains. Mallee scrub areas with Black Box (E. largiflorens) or Belah (Casuarina cristata) trees are also occupied.

In parts of it’s southeast range, the Regent Parrot has adapted to orchards, vineyards, and other cultivated land. However, the destruction of native woodland habitats remains the primary threat to this vulnerable subspecies.

Across their habitats, Regent Parrots typically roost and nest in the hollows of large, mature eucalyptus trees. Nesting areas are usually located close to a water source or wetlands.

Diet and Feeding

The Regent Parrot is adapted to feed on a wide variety of native seeds, fruits, buds, and blossoms. Their diet varies somewhat between the natural vegetation of the inland semi-arid region versus the more fertile riparian habitats.

Natural Diet

- Seeds of eucalyptus, acacia, native grasses, and other trees/shrubs

- Fruits including figs and mistletoe

- Leaf buds, flowers, and nectar

- Some insects and larvae

The southwest birds consume more dryland species like saltbush and cypress pine, while southeast parrots feed on riparian zone vegetation. The latter also make more use of cereal crops like wheat, oats, and barley, especially windfall grain.

Orchard fruits and planted nut trees may provide supplementary food as well. Regent parrots have proven very flexible in adapting to non-native garden plants and agricultural areas.

Feeding Behavior

- Forage predominantly on the ground for grass seeds in open spaces

- Also glean the canopy of trees and shrubs

- Dig in loose soil for bulbs and tubers

- Feed in early morning and late afternoon

- Form small flocks of 2-20 birds that may mix with other parrots

- Flock size can reach 60+ birds when food is abundant

Their long curved bill is well-adapted for cracking hard seeds and tearing apart fleshy fruits. Strong legs and feet allow them to readily walk and run on the ground while foraging.

Regent parrots do not have a specialized brush-tipped tongue for nectar, but will supplement their diet with flower bits and pollen. TheirRole in seed dispersal likely aids the trees and plants of their arid habitat.

Breeding and Reproduction

The Regent Parrot breeds during the Australian spring and summer months from August through January. It shows typical parrot behaviors in forming strong monogamous pairs and utilizing tree hollows for nesting.

Nest Sites

Regent parrots nest in natural tree hollows, often located in large eucalyptus trees along watercourses. The hollow chambers used are very deep, sometimes over 15 feet inside the trunk or a thick lateral branch.

Southeast birds favor River Red Gum trees, while southwest birds use hollows in old Salmon Gums, Gimlet trees, and Wandoo among others species. The entrance hole ranges from 3-5 inches wide.

Clutch Size

Usual clutch size is 4-6 white rounded eggs. On average the eggs measure:

- 1.2 inches long by 0.9 inches wide (31 x 24.5 mm)

The female develops an egg every 3 days before starting incubation when the clutch is complete.

Incubation and Fledging

Only the female incubates the eggs, for approximately 20-21 days. She leaves the nest hollow rarely during this period as the male brings food.

Once hatched, both parents tend the altricial nestlings providing regurgitated food. Nestlings fledge at around 5-6 weeks old but remain dependent on parental care for some time after exiting the hollow. They reach full adult plumage by 13-18 months old.

Pairs may manage two broods per breeding season when conditions allow. Established pairs often reuse the same nest site across years showing site fidelity.

Behavior and Ecology

The Regent Parrot exhibits typical parrot behaviors but also shows some unique adaptations to the dry interior regions of Australia.

Social Structure

Regent parrots form permanent monogamous pairs that remain together across breeding seasons. However, they also gather in larger flocks at various times:

- Small feeding flocks of 2-20 birds

- Larger roosting flocks up to 100+ individuals

Mixed flocks may form with other parrots like rosellas or ringnecks in areas of abundant food.

Flight and Acrobatics

In flight, these long-tailed parrots are graceful but also swift and agile. Their wings allow effortless maneuverability amongst the eucalyptus trees and shrubs.

Groups put on active displays of aerial acrobatics near dawn or dusk including:

- Swift dives and dashes

- Tight spiraling in pairs

- Upside down flipping

Thermoregulation

Regent parrots use evaporation to cool their bodies in hot weather. They drink and bathe regularly by dipping wings into water sources. Seeking shade and regulating activity patterns aids their survival in arid climates.

Communication

Vocalizations are typical loud parrot squawks and shrieks. Their characteristic contact call sounds like a rolling “carrak carrak.” Regent parrots generally feed and roost noisily as a flock.

Visual displays reinforce pair bonds. Courting males direct eye, beak, feather and foot movements toward the female. Color changes also communicate moods from excitement to aggression.

Overall, the Regent Parrot remains somewhat wary of humans in the wild but bold and interactive around their own flock. Their social bonds and adaptations aid resilience even in harsh inland habitats.

Conservation Status

The Regent Parrot species as a whole is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. However, the southeast Australian subspecies P.a. monarchoides is listed as Vulnerable under Australia’s national EPBC Act.

Population numbers for the southwest subspecies are estimated between 10,000 to 20,000 mature birds. They remain locally common within their Australian range.

In contrast, the southeast mainland subspecies has suffered concerning declines:

- Total population estimated between 600 – 1,700 adult birds as of 2018

- Marked drops since the 1980s linked to habitat destruction

Major threats contributing to the endangered state of P.a. monarchoides include:

- Clearing and fragmentation of crucial River Red Gum riparian forests

- Loss of nesting trees and landscape homogenization

- Effects of livestock grazing and agriculture on understory

- Trapping for the pet trade

- Vehicle collisions in rural areas

Ongoing conservation efforts seek to curb declines and support recovery:

- Habitat restoration projects

- Nest site protections and monitoring

- Restrictions on capture from the wild

- Raising captive-bred birds for aviculture

Maintaining resilience of the southeast dryland ecosystems remains vital for the vulnerable namesake subspecies. Their specialized habitat needs demand thoughtful regional planning to prevent the Regent Parrot from requiring a higher threat category in the future.

Cultural Significance

The vibrant beauty of the male Regent Parrot has inspired human appreciators of Australia’s unique wildlife for nearly 200 years. Early European artists and ornithologists like John Gould and Edward Lear featured the species in their folios long before photography could capture fine details.

Symbolism and Art

The striking plumage lends it’self well to indigenous artwork and handicrafts. Regent Parrot motifs often signify:

- Joy, playfulness, curiosity

- Brilliance, talent

- Partnership, community

Stylized Regent Parrot designs appear on fabrics and in logos for local organizations. SOFT illustrations may represent the parrot’s habitat and conservation causes.

Aviculture

The Regent Parrot adapts readily to captivity when hand-raised. Their beauty, qualities as exhibit birds, and occasional talking ability make them desirable aviary species. However, the vulnerable wild population of the southeast subspecies means only captive-bred birds can be ethically acquired.

Responsible aviculturalists provide proper enclosures, social groups, nest boxes, and specialty diets. Studbooks help manage captive genetic diversity regionally. Captive rearing and releases aid some recovery efforts where appropriate.

Eco-Tourism

Birding tours striving to spot Regent Parrots responsibly generate tourism activity near protected parks and reserves. Seeing the rare seaborn fly in native River Red Gum habitat offers a uniquely Australian wildlife experience. Such ecotourism also promotes continued conservation investment benefitting both local economies and endangered species.

From indigenous art to aviaries worldwide, the Regent Parrot remains an iconic ambassador for Australia’s spectacular but threatened wildlife. Ongoing cultural appreciation can support expanded habitat protections to ensure thriving wild populations.

Conclusion

The Regent Parrot stands out as one of Australia’s most striking parrot species thanks to the male’s vibrant plumage of bright yellow contrasting with wings and tail of shiny blue-black. Yet this beauty also leads to continued threats from illegal capture and habitat loss, requiring active conservation efforts especially on the southeast mainland.

While still locally common in the southwest, the total population of P. anthopeplus monarchoides has dwindled to under 2,000 mature adults restricted to scattered River Red Gum riparian forests and adjacent mallee lands. Their specialized nesting habits and diet make them vulnerable as development alters historic floodplain woodlands. Continued clearing also degrades inland drylands, fragmenting crucial feed and roost locations.

Increased legal protections, captive breeding, climate-wise habitat restoration, and community support for the Regent Parrot’s unique dryland ecosystem niche can help prevent deterioration into a higher threat category. Maintaining healthy connectivity along inland river corridors allows the dispersal behaviors key to their ecology in an arid environment subject to volatile seasonal conditions.

From indigenous art to vineyards where the birds add a flash of golden wings, traditional Australian country culture intertwines with the Regent Parrot’s presence. Losing this vulnerable namesake of the Murray-Darling Basin would also erase an iconic component of the nation’s natural heritage. By balancing human activity with the needs of sensitive dryland species, sustainable conservation management provides hope for the continued survival of the beautiful Regent into the future.