St. Vincent Parrot (Amazona guildingii)

The island nation of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in the Caribbean Sea is home to an array of stunningly colorful parrots. But perhaps the most impressive of them all is the Saint Vincent Parrot, also known as the Saint Vincent Amazon.

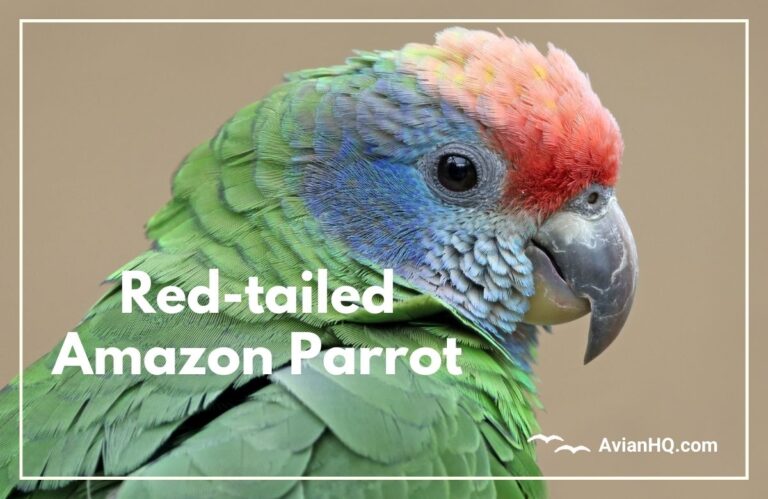

With it’s vivid green, yellow, blue and bronze plumage, this parrot measures about 16 inches (40 cm) long and weighs between 23-25 oz (650-700 g). It has captivated bird enthusiasts for decades with it’s beauty and has graced the national coat of arms due to it’s cultural significance.

“The St. Vincent Parrot is a true jewel of the Caribbean. It’s brilliant colors sparkle like an emerald against the lush green forests it calls home.”

You’ll find this rare parrot living in the moist, mature forests of St. Vincent island, hiding high up in the canopy at elevations between 410-3280 ft (125-1000 m).

It prefers to feed on particular trees like the Dacryodes and Ficus species. Though normally occurring in flocks, pairs will break away to nest and zealously defend their tree hollows during breeding season.

Sadly, several threats have greatly impacted the St. Vincent Parrot. From habitat loss to hunting and trapping, it’s population has dwindled to less than 1000 birds in the wild. Conservation efforts are underway to protect this Vulnerable species and it’s limited island habitat.

This article will cover all there is to know about this national treasure of St. Vincent island that has captured attention across the world. Let’s explore deeper into the life and behaviors of this majestic parrot.

History and Taxonomy

The St. Vincent Parrot was first discovered scientifically in 1817 by Reverend Lansdown Guilding during an expedition to the island. He named the species after himself as Psittacus guildingii, later changed to the current scientific name of Amazona guildingii.

The common name recognizes the parrot’s limited range on St. Vincent island in the Caribbean’s Lesser Antilles islands. No subspecies of the St. Vincent Parrot have been identified.

The species was later featured in works by prominent naturalists like Charles Darwin and John Gould, further bringing attention to this uniquely colored Caribbean parrot.

Its scientific name breaks down as follows:

- Genus: Amazona – Refers to New World parrots in the amazon group

- Species: guildingii – Named after Rev. Lansdown Guilding who first described it

So in essence, Guilding’s Amazon parrot reflects both the descriptor who discovered it and the group of parrots to which it belongs.

Physical Appearance

The St. Vincent Parrot is a medium-large sized parrot growing up to 16 inches (40 cm) long. It weighs between 23-25 ounces (650-700 grams).

Its plumage features an array of vivid colors. The forehead, area around the eyes and throat are yellowish-white and orange. The ear coverts, cheeks and nape display bright blue and green hues.

The back, wings and tail feathers shine in shades of olive-green, purple-blue and bronze-brown. The tail tips and wing edges glow a vibrant orange and yellow.

There are two color variations or morphs of this parrot species. The more common morph has the yellow and brown plumage, while the rarer morph is mostly green.

In both morphs, the sturdy bill is a horn color. The eyes are reddish-orange surrounded by grey eyerings. And the feet are grayish in color.

Juvenile birds look similar but with duller versions of the adult plumage. Their iris eye color is brown at first.

So in flight, the St. Vincent Parrot dazzles with a rainbow of colors flashing across it’s wings and tail. These markings make it unmistakable from other regional parrots.

Habitat and Distribution

The St. Vincent Parrot is endemic to the Caribbean island of St. Vincent in the Lesser Antilles chain. It is found nowhere else in the world but this single island, making it’s range extremely limited.

This species inhabits dense, mature moist forests at higher elevations between 410-3280 ft (125-1000 m). It’s habitat lies specifically in the upper western and eastern mountain ridges of St. Vincent’s Soufrière volcano.

The parrots prefer old growth forests filled with tree varieties like the Dacryodes, Ficus, and Cecropia that provide nesting sites and food sources. Though normally restricted to these mountain forests, they will occasionally visit cultivated lands and gardens.

Within their dwindling montane forest habitat, St. Vincent Parrots occur in the greatest numbers in the Colonarie Forest Reserve in the southwest and the Cumberland Forest Reserve in the north. Continued preservation of these protected reserves is vital for the parrot’s survival.

Sadly the species has not been successfully introduced to any other locations, even captive breeding centers. A small population did exist at the Graeme Hall Sanctuary in Barbados briefly. But issues like poaching, lack of resources, and minimal government support prevented long-term establishment.

So the St. Vincent Parrot persists solely in it’s native forest habitat on St. Vincent island, making conservation of this diminishing refuge all the more critical.

Diet and Feeding

The diet of the St. Vincent Parrot consists primarily of fruits, nuts, flowers, and seeds. It uses it’s strong bill to crack hard nuts and seeds.

Some of the main food plants include:

- Fruit trees: Fig, Palm, Sloanea, Meliosma

- Nut trees: Dacryodes, Simmons

- Flowering trees: Eucalyptus, Ixora

- Cecropia – Provides fruits and nesting sites

The parrots display a range of feeding behaviors while foraging in the forest canopy. They can be seen plucking fruits directly from branches or gathering fallen nuts on the ground.

Flocks will actively climb and hop between trees searching for ripening food items. Once found, they will gorge themselves alongside fellow flock members.

Breeding pairs are especially active foragers during nesting season to provide plenty of nutrition for their chicks. They follow reliable food sources across their home range.

In recent years, the parrots have adapted to visiting agricultural plots and gardens near their habitat. Farmers often detect flocks raiding domestic fruit trees. This behavioral shift may indicate changes in the availability of natural food plants.

By following seasonal crops and tree fruiting patterns, the St. Vincent Parrot is an adept diner able to shift it’s diet as needed. But conservation of it’s core native food trees remains essential to sustain this species in the wild.

Breeding and Reproduction

The St. Vincent Parrot nests in tree hollows, favoring old growth trees like the Dacryodes and other large diameter species. The nesting site is typically high up with a narrow entrance hole.

Breeding pairs break away from the main flock and defend the area around their chosen nest tree during the breeding season. They will aggressively chase away other birds or animals near the nest.

The breeding season runs from February to June each year. The female lays a clutch of 2-3 white eggs in the protected cavity. The eggs measure roughly 1.8 x 1.5 inches (46.5 x 39 mm) in size.

She then incubates the eggs for 25-26 days before they hatch. Both parents help to feed and care for the young chicks.

The babies fledge at around 9-10 weeks old. But they continue to be fed and taught to forage by the dedicated parents for several months after leaving the nest.

The breeding success and output of the St. Vincent Parrot is low, like many parrot species. It may take years for newly matured birds to obtain a suitable nest site and mate. Plus clutch loss from storms, predators, and timber harvesting further limit reproductive rates.

These challenges and threats to successful breeding make conservation of protected nesting reserves integral for population stability. Continued support is needed to monitor and safeguard known nest trees across their specialized habitat.

Behavior and Ecology

The St. Vincent Parrot exhibits highly social behaviors, normally gathering in large flocks of 20-30 birds. They fly together through the forests calling loudly to coordinate foraging and roosting activities.

These flocks display a level of cooperation between members. Young fledglings learn essential skills like feeding, predator awareness, and flight by watching and interacting with older parrots.

Strong social bonds seem to form given their prolonged associations in roaming flocks. Yet a strict hierarchy also exists with dominant leaders dictating movements.

Outside of breeding season when nesting areas are fiercely protected, the flocks allow somewhat overlapping home ranges while congregating at ample food sources. But they may break into smaller subgroups of 5-10 temporarily before rejoining the flock.

In addition to loud vocalizations, the parrots make a variety of other noises like squawks, honks, and trumpeting calls. These likely serve communication functions related to warnings, food detection, defending resources, and reproducing.

Though the St. Vincent Parrot remains moderately well-studied, much is still unknown about the ecology of this species. Their interactions and competition with other wildlife sharing their habitat have not been fully documented.

Continued field research into daily and seasonal movement patterns, population densities, threat responses, and adaption abilities can support updated conservation actions for their evolving forest ecosystem.

Conservation Status

Due to ongoing population declines, the St. Vincent Parrot is currently classified as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It’s wild population is estimated to be less than 1000 individuals and dropping.

Major threats contributing to their endangered status include:

- Habitat loss from deforestation, logging, agriculture

- Over-hunting for food and the pet trade

- Nest poaching and capture of chicks

- Invasive species predation and competition

- Stochastic hurricane events

In response, St. Vincent created protected forest reserves starting in the 1970s with support from conservation groups. These guarded reserves defend nesting and feeding grounds.

Additionally, the St. Vincent national government, alongside the Forestry Department and the Botanical Gardens, operate a captive breeding program on the island. Though small in scope, it offers a backup population for reintroduction if needed.

The species receives strict protections under CITES Appendix 1, forbidding international commercial trade. And it holds cultural value as the national bird featured on the St. Vincent coat of arms.

Yet despite protections, the several interacting threats make the last remaining habitat precarious for the St. Vincent Parrot’s persistence. Expanded reserves, anti-poaching measures, sustainable forestry policies, and a bolstered captive group are still required to secure this parrot’s future in it’s native home.

Cultural Significance

The vibrant St. Vincent Parrot holds a prestigious place as the national bird of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. It appears alongside the national flower, the Soufriere Tree, on the country’s coat of arms.

This handsome parrot had value since early times to the indigenous peoples and was likely kept as a pet. Early European settlers and colonists also captured the birds for trade abroad to Europe and other islands.

Throughout the 18th and 19th century, the St. Vincent Parrot was targeted by the pet bird market for it’s beautiful colors, singing ability, and impressive size. Trappers decimated wild flocks to sell chicks domestically or for export.

Unfortunately, this unchecked practice continued into modern times. By the 1990s, extensive poaching and habitat loss left the species in danger of extinction. Only dedicated conservation efforts helped stabilize the shrinking population.

While no longer legally trapped, the parrot remains an ingrained cultural symbol across St. Vincent. It adorns the national currency, postage stamps, and handicrafts sold to tourists. Nature tours to see the parrots help drive eco-tourism.

To Vincentians, this rare endemic bird represents their lush island home and serves as a breathtaking reminder for conservation of their fragile forests that sustain this beloved icon.

Conclusion

The St. Vincent Parrot stands out as one of the most striking amazon parrots among it’s kind. It’s vibrant plumage reflecting emerald forests and sapphire skies has captured attention across decades.

Yet this 16 inch (40 cm) long parrot survives only on it’s lone Caribbean island home of St. Vincent by clinging to a diminishing stretch of mature montane rainforest.

From feeding on specialized fruits and nuts to nesting high in old tree hollows, the species depends fully on this isolated habitat. Loss of critical food and nesting resources threatens the parrot’s persistence despite protective actions.

With less than 1000 birds remaining, intensive conservation is still needed to preserve the home of this national icon. St. Vincent Parrots serve as an indicator for the health of Caribbean island forests being altered by invasive species, climate shifts, over-exploitation, and encroaching human activity.

Protecting viable populations of this Vulnerable parrot ensures deeper integrity of the forests and biodiversity across this volcanic island. The fate of the St. Vincent Parrot remains uncertain, but continued forest conservation offers some hope of securing the island’s feathered treasure.